Before CGI in "Star Trek" and "Star Wars"

A look at how "Star Trek" and "Star Wars" used models, matte paintings, and inventive craftsmanship to create unforgettable worlds before the age of CGI.

Setting the Stage: Science Fiction Before CGI

From the mid-1960s through the late 1970s, the science fiction worlds seen on screen were built not with computers, but with cameras, paint, lights, and the steady hands of craftsmen.

Every alien vista and starship had to be created in front of or directly onto film. Mechanical rigs, optical compositing, and matte paintings were the core tools of the trade. These methods were demanding, but they gave the genre a tactile authenticity that still resonates today.

"Star Trek" (1966–1969) brought interstellar travel to television audiences through a mix of scale models, painted backdrops, and clever lighting. The show’s modest television budget meant that effects had to be both quick to produce and convincing enough to carry the viewer into another world. "Star Wars" (1977) took this craftsmanship to a cinematic scale, combining miniatures, motion-control cameras, and dense soundscapes to create a galaxy that felt vast and lived-in. Neither production relied on a single frame of digital imagery.

The constraints of the era became a catalyst for ingenuity. Artists and technicians had to solve complex visual problems with physical solutions, often inventing new techniques on the spot. Out of these limitations came some of the most iconic images in science fiction, crafted with precision and imagination rather than processor power.

Model Makers and Motion Control

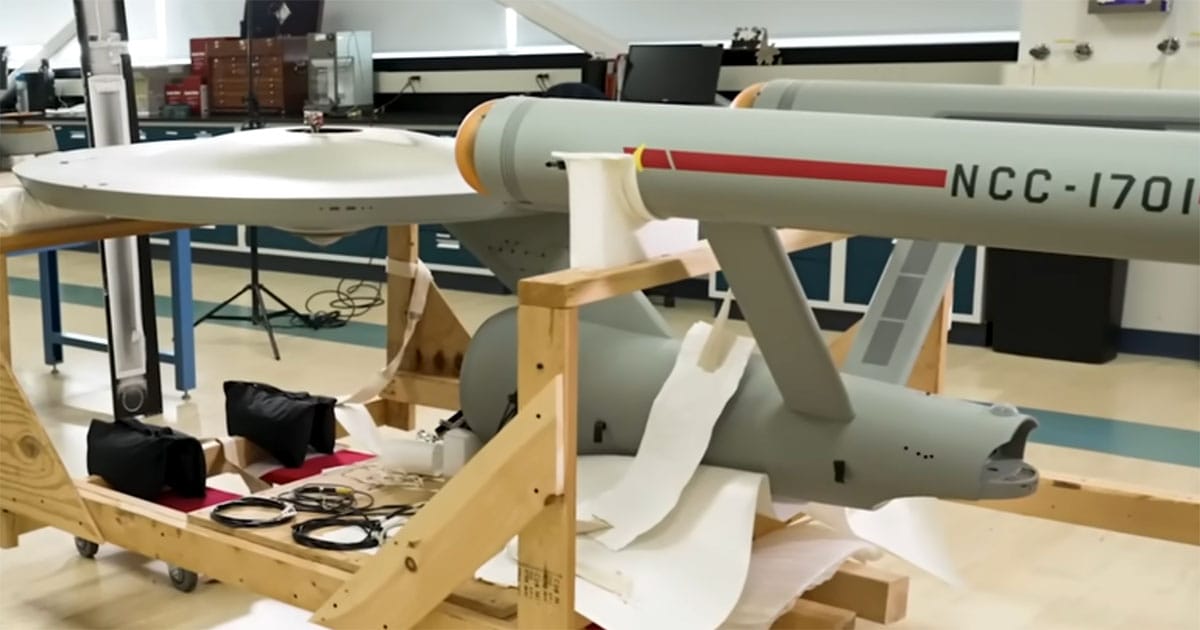

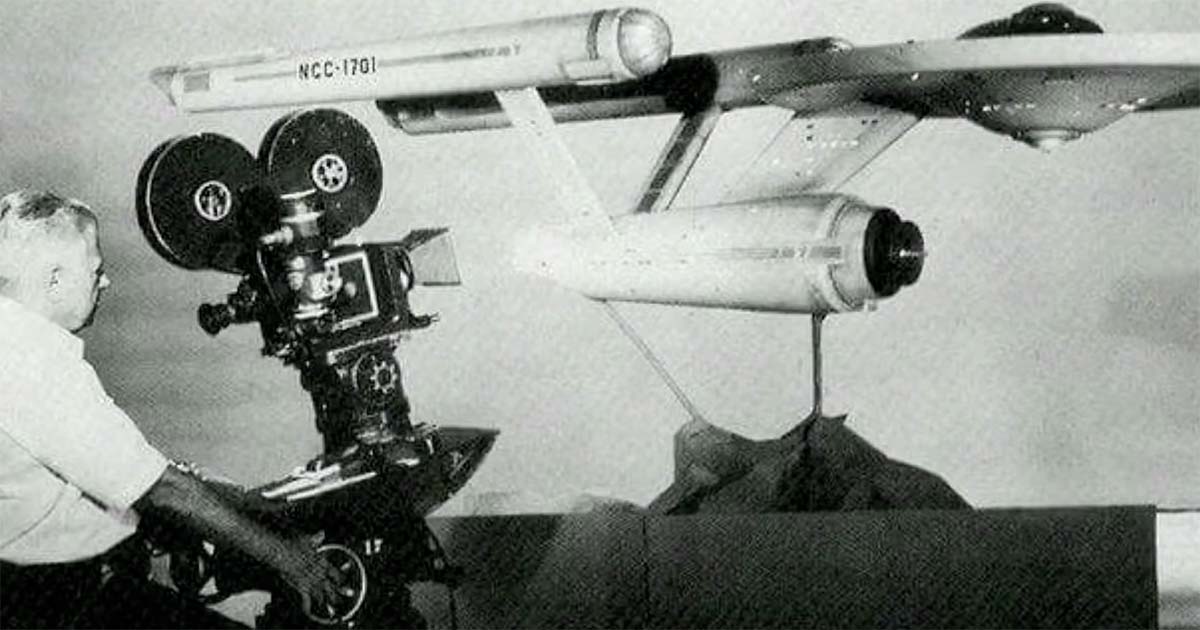

In "Star Trek," the USS Enterprise was a handcrafted miniature over eleven feet long, suspended on a mount and lit with internal bulbs to suggest glowing warp nacelles. Camera crews filmed the model from different angles against a star field, with slight camera moves giving the illusion of the ship gliding through space.

For scenes requiring dynamic movement, the production often combined static shots with optical effects, layering elements together in the lab. This approach allowed a weekly television series to present a convincing starship on a strict budget.

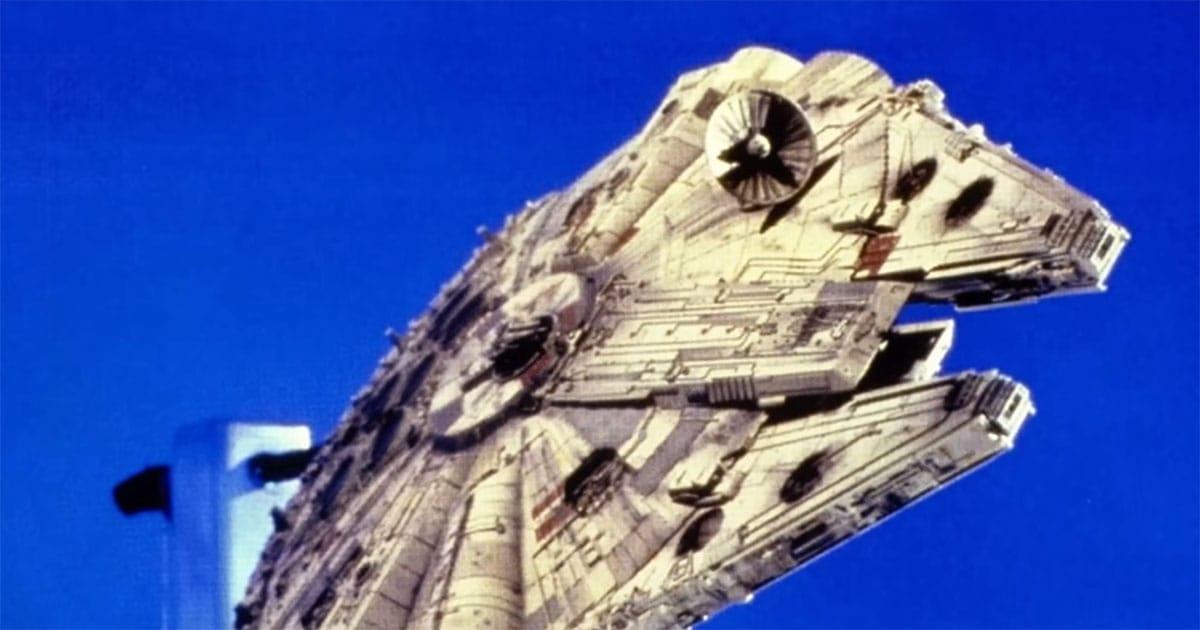

By the time of "Star Wars," George Lucas and his team at Industrial Light & Magic were ready to push miniature photography into new territory. The Dykstraflex camera system, designed by John Dykstra, could repeat precise moves over and over, allowing multiple passes on the same shot for compositing.

This made it possible to film complex dogfights between X-wings and TIE fighters, each element shot separately and then combined into a single seamless image. The ships themselves were built using a technique called kit-bashing, in which parts from off-the-shelf model kits were integrated into custom designs.

This combination of fine craftsmanship and mechanical precision gave "Star Wars" an unmatched sense of motion and scale. It was not enough for the models to look good up close—they had to move like real machines in a vast, weightless void.

Matte Paintings and Forced Perspective

Matte paintings were one of the most powerful tools in the pre-CGI era, transforming limited sets into sprawling alien worlds. In "Star Trek," painted backdrops often extended the edges of a planet’s surface or added distant structures, making studio soundstages feel like uncharted landscapes.

Artists matched lighting and color so carefully that viewers rarely noticed the transition from physical set to painted illusion. These static images gave the series a scope it could not have achieved otherwise.

"Star Wars" used matte paintings to create vast hangar bays, towering palace interiors, and the sweeping skyline of Cloud City. Artists like Ralph McQuarrie and Michael Pangrazio painted directly onto glass, allowing live-action elements to be integrated with artwork in a single composite shot.

The result was environments that felt both monumental and believable, even when no such sets existed. This method allowed the production to go beyond the physical limitations of a soundstage.

Forced perspective added yet another layer of illusion. In "Star Trek," sets were designed with narrowing hallways and adjusted lighting to make them seem longer than they were. Props and background elements were scaled down to suggest distance. Combined with matte paintings, these techniques expanded worlds without expanding costs, keeping the viewer’s imagination fully engaged.

Resourcefulness and Reuse

On "Star Trek," economy often meant creativity. Costumes were altered, props were repainted, and entire set pieces were reconfigured from one episode to the next. A corridor on the Enterprise might appear again as part of a space station, with only minor changes to lighting and wall panels. This recycling was not just practical—it helped maintain a consistent visual language across the series.

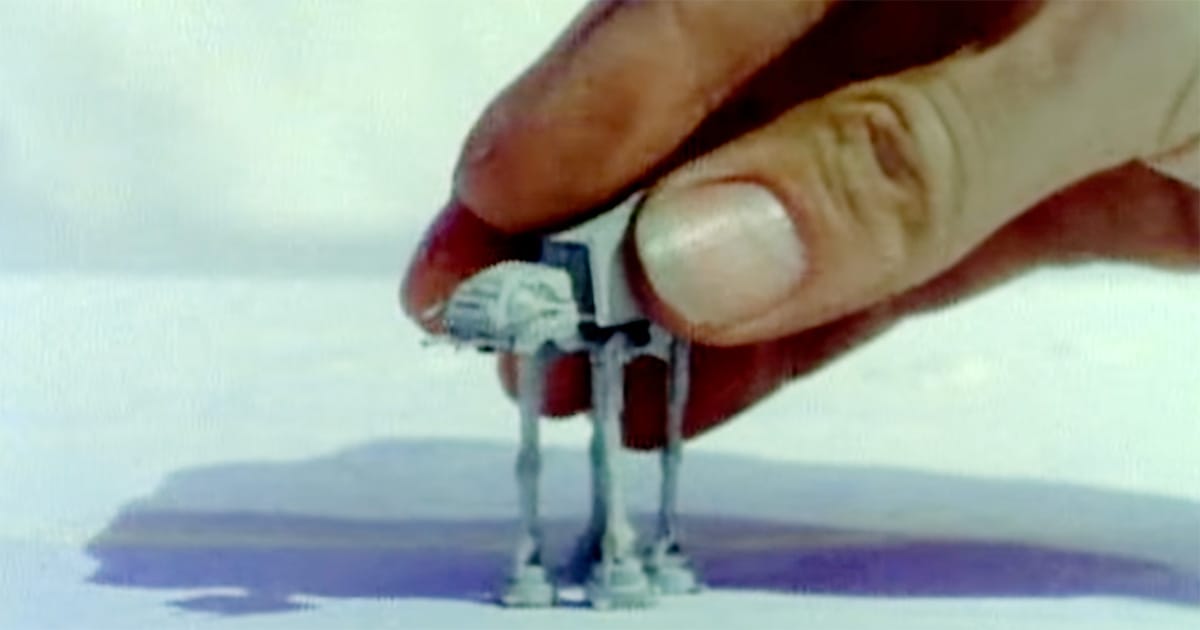

"Star Wars" took a similar approach in its own way, most notably through kit-bashing. Model makers combined parts from tank, airplane, and car kits to add intricate surface detail to ships and vehicles. The practice gave the machinery of the galaxy a layered, functional look without the expense of designing every piece from scratch. Some model components appeared multiple times, hidden in plain sight on different craft.

In both productions, the act of reusing materials was less about cutting corners and more about making the most of what was at hand. The limitations of time and budget became a driving force for innovation. When viewed today, these reused elements often feel like part of a larger, unified world rather than separate, recycled parts.

Ingenuity in the Age Before Pixels

The influence of pre-CGI craftsmanship still reaches into modern science fiction filmmaking. Directors who value tactile realism continue to use miniatures, physical sets, and in-camera effects to achieve a sense of authenticity.

Productions like "The Mandalorian" and the recent "Star Trek" series have blended digital tools with practical techniques, showing that the older methods still have a place in the industry. This continuity keeps the link to an era when every image was built by hand.

"Star Trek" and "Star Wars" proved that compelling worlds could emerge from determination and problem-solving rather than unlimited resources. Their teams used the materials of their time to create images that remain iconic decades later.

Many of these techniques were born out of necessity, yet they have endured because they work. The sense of depth, weight, and presence achieved by physical effects is difficult to replicate in a computer.

Looking back, it is clear that the era before CGI was not a limitation—it was a forge. It shaped a generation of artists who understood that imagination alone is not enough. The craft lies in making that imagination tangible, one frame at a time, with the tools and ingenuity at hand.