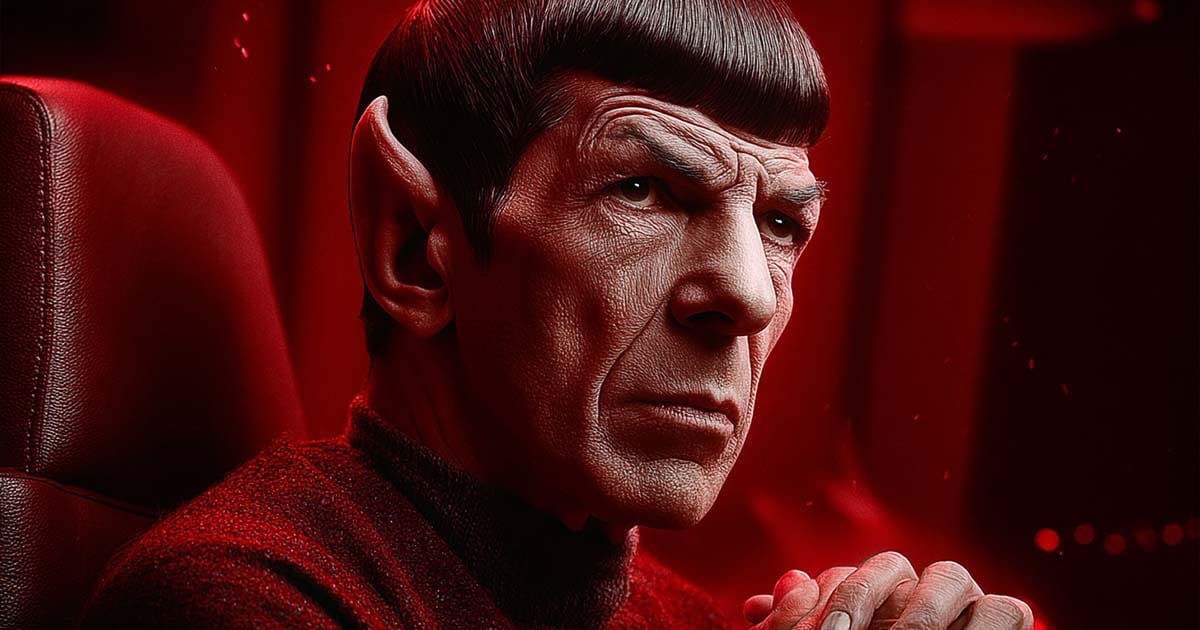

Spock Almost Had Red Skin

Mr. Spock of "Star Trek: The Original Series" was nearly given red skin, but 1960s TV technology made him appear demonic, leading producers to craft the subtler look that became iconic.

In the long shadow of television history, there are moments when a single design choice could have altered everything. One such moment came during the early production of "Star Trek: The Original Series," when Gene Roddenberry and his team considered giving Mr. Spock bright red skin. The thought was simple. Audiences needed to see at a glance that Spock was alien, and a crimson face offered an immediate visual distinction without the need for elaborate prosthetics.

The earliest concept sketches leaned into this idea of Spock as exotic and unsettling. Alongside his pointed ears and arched eyebrows, the addition of a red hue gave him the unmistakable air of a devil. In those drawings, he looked less like a first officer and more like a character who had stepped out of medieval folklore.

Roddenberry envisioned him as a creature who carried the wisdom of the stars, yet looked disquieting enough to remind viewers that he was not entirely of their world.

Makeup tests soon revealed a serious flaw. On color television cameras, Spock’s red face appeared bold enough. But in 1966, many American households still owned black-and-white sets. On those screens, the makeup collapsed into darkness, rendering Nimoy’s features a flat black. Combined with the ears and brows, the image was no longer alien—it was downright demonic. Executives at NBC worried that parents might see Spock as satanic, a risk they were unwilling to take for a series already viewed as unconventional.

The decision was made to soften his appearance. Out went the crimson hue. In its place came a more subdued look, a pale tint with just the faintest suggestion of green to hint at copper-based blood. The devil’s mask gave way to something far more subtle. Spock would remain visually distinct, but his strangeness would not overwhelm the screen. This balance of alien and familiar became the cornerstone of his enduring appeal.

Leonard Nimoy’s performance filled the space the makeup abandoned. With no garish design to lean on, he conveyed Spock’s difference through voice, bearing, and restraint. The choice elevated the character beyond a painted oddity. Viewers saw a man caught between two worlds, one of emotion and one of reason, and they connected with his inner conflict. His alien features became a frame, not a cage, for the depth of his portrayal.

Looking back, the red-skinned Spock belongs to the archive of unrealized television history, alongside other discarded concepts that might have derailed a classic. Had the crimson survived, Spock might have been remembered as a gimmick rather than a figure of quiet strength. Instead, restraint prevailed, and audiences were introduced to a character whose depth of humanity shone brighter than any makeup.

The lesson is simple. Sometimes the boldest decision is the one not taken. By stepping back from theatrical excess, Roddenberry and his team preserved the dignity of a character who would become a cornerstone of American science fiction. Spock’s appeal was never in the color of his skin but in the logic of his mind and the loyalty of his heart.