The Day Luke Skywalker Met a Real Snake

Mark Hamill once said a snake bit him while filming “The Empire Strikes Back.” This behind-the-scenes story reveals how real danger helped make Dagobah one of Star Wars’ most vivid worlds.

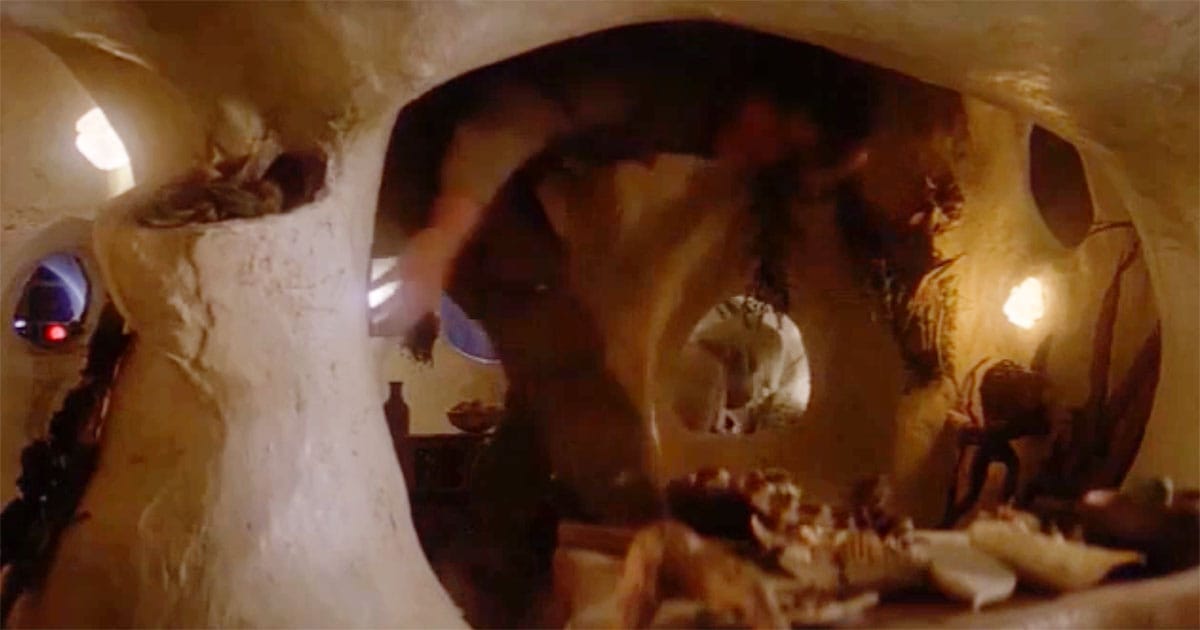

The swamp of Dagobah was never real, but it felt real enough. Warm lights baked the mud, fog rolled across the floor, and somewhere beneath the rubber vines, something hissed. For Mark Hamill, who had already faced the Dark Side, this was the kind of danger that didn't come from a script.

The year was 1979, and "The Empire Strikes Back" was deep in production at England's Elstree Studios. The Dagobah set was a triumph of old-fashioned ingenuity—a man-made marsh filled with mist machines, puppets, and live creatures. Director Irvin Kershner wanted it to look alive, so he asked for real snakes. The decision gave the swamp its eerie pulse and, as it turned out, one small surprise.

A Bite or Just a Brush

Years later, Hamill recalled what happened. One of the snakes, blind from molting, had been handled during a take. "It flinched each time I touched him," he said. "After several takes, he got fed up and bit me." Hamill shared the story with the kind of amusement only time allows. It was a tiny bite, a passing moment, yet it became part of the film's quiet mythology.

There's no studio record of the incident, and some crew members remember things differently. Still, it fits the atmosphere of those long days under the hot lights, where mud mixed with sweat and cables tangled beneath the water. The work was physical and unpredictable. That was the price of realism before digital effects made danger optional.

Frank Oz, who performed Yoda, once said that Kershner wanted "the back of the hut alive with movement." The snakes gave the set its sense of unease—the feeling that this strange world could reach out and touch you. In that context, a startled reptile making contact with the film's hero doesn't seem far-fetched at all.

The beauty of that production era was its lack of safety nets. If a smoke machine clogged or a creature refused to cooperate, the crew improvised. When Hamill says he was bitten, one can almost picture a weary assistant quietly fetching a bandage while the camera kept rolling. It was that kind of movie—built on momentum, not perfection.

The Craft Behind the Magic

If anything, the story of the snake bite captures the spirit of the Star Wars generation of filmmaking. Everything was practical, improvised, and built by hand. These were artists working in the mud, chasing something that felt bigger than the technology they had. Every drop of water and coil of smoke on screen was the result of real effort.

The Dagobah scenes became a touchstone for the power of practical effects. Yoda wasn't a computer creation but a puppet operated by human skill and patience. Hamill had to act opposite a character brought to life by rods, wires, and craftsmanship. In that environment, a snake bite—real or not—felt like part of the method.

Hamill's attitude toward the event says much about the time. There was no panic, no insurance claim, no social media debate. Just an actor doing his job, then laughing about it decades later. The story lingers not because it was dramatic but because it was human.

Science fiction often celebrates the extraordinary, yet its magic depends on people willing to endure ordinary discomfort to make it believable. Somewhere in the middle of that swamp, Luke Skywalker met a real snake. Whether it was a true bite or a gentle nip hardly matters now. What matters is that the danger felt authentic—and for a moment, the fantasy bit back.