The Secret Origin of the Vulcan Salute

Leonard Nimoy’s Vulcan salute in "Star Trek" draws from a Jewish blessing, adding unexpected spiritual depth to Spock’s character and enriching the cultural fabric of the series.

The Blessing Behind the Salute

There's a curious power in gestures. Some are ancient, others accidental, and a few manage to span cultures and galaxies. One of the most iconic gestures in science fiction—perhaps in all of television—is the Vulcan salute. But its origin is not a footnote in Hollywood trivia. It is a story of heritage, insight, and Leonard Nimoy's uncanny ability to shape myth from memory.

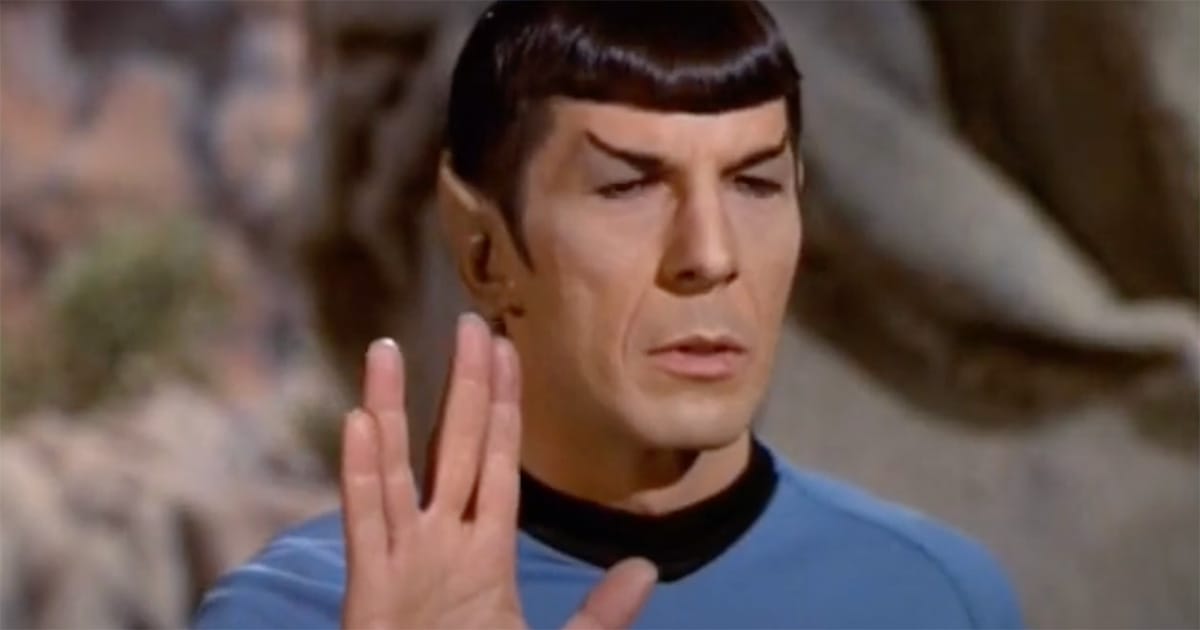

When viewers first saw Mr. Spock raise his hand in "Amok Time" (1967), forming a V with his fingers and uttering the phrase "Live long and prosper," they witnessed more than a moment of alien etiquette. They saw a trace of something sacred. Leonard Nimoy, who portrayed the half-human, half-Vulcan science officer aboard the USS Enterprise, borrowed the gesture from his own Jewish upbringing. Specifically, from a childhood memory of a synagogue ceremony that left a deep impression.

In traditional Jewish services, descendants of the priestly tribe—the Kohanim—extend their hands to deliver the Priestly Blessing. The fingers are spread to form the Hebrew letter Shin. That letter stands for Shaddai, one of the names of God. It is a powerful moment meant to be glimpsed with awe or not at all. Young Nimoy peeked, and decades later, he remembered.

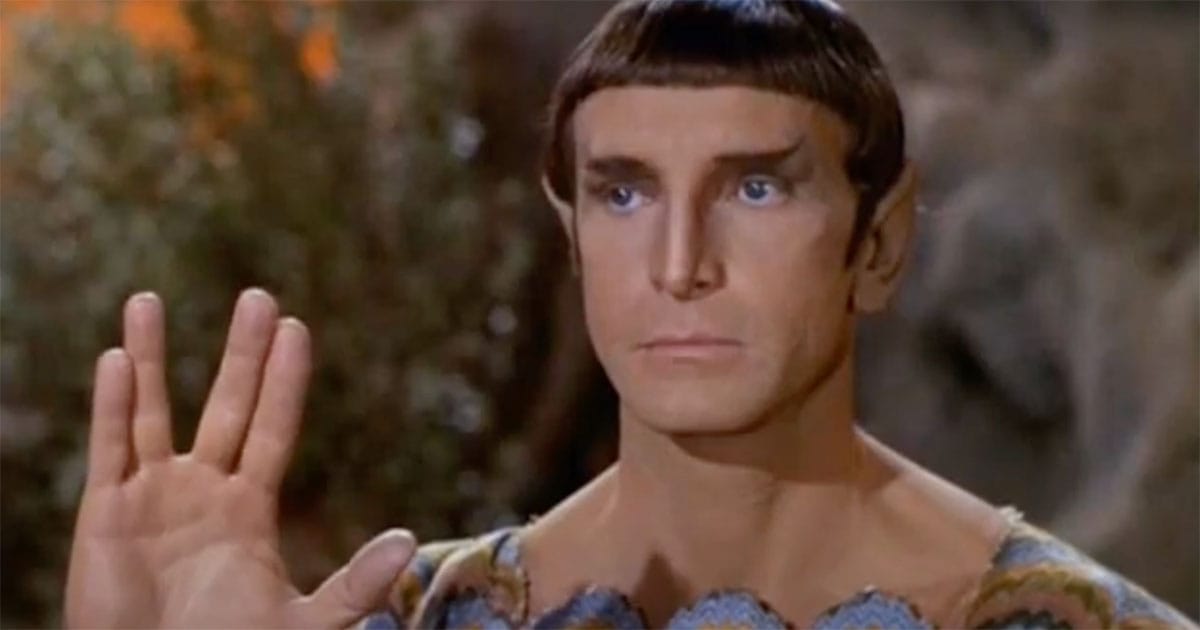

Rather than invent an alien greeting from scratch, Nimoy folded this real-world symbol into the culture of the Vulcans. The effect was profound. In one quiet motion, the Vulcans gained history, spirituality, and discipline. It told the audience that Vulcans were not just logical. They were ceremonial, rooted, and restrained. The gesture sets Spock apart from the more brash humans around him and makes him more believable as a man of two worlds.

Gene Roddenberry had not scripted the salute. It was Nimoy's contribution, which was improvised and then adopted. The production team did not realize they had just added a permanent fixture to the language of science fiction. But the fans noticed. And they practiced it—some succeeding, others failing to contort their fingers. What began as a whisper from an ancient liturgy became a badge for thinking men, dreamers, and engineers alike.

This is one reason "Star Trek" continues to resonate. It is not just about warp drives and phaser banks. It is about the quiet decisions that lend texture to a galaxy. The Vulcan salute was not designed in a studio boardroom. It was remembered. Nimoy did not just play an alien. He believed in the possibility of cultures as rich and strange as our own. And he brought that belief into the script one gesture at a time.

In the end, Spock's hand signal became something larger than either Vulcan lore or Jewish ritual. It became a universal expression of goodwill and longevity, bridging belief systems and star systems alike.

It is a reminder that in the right hands, science fiction does not have to invent everything. Sometimes, it only needs to remember.