V’Ger the Most Overlooked Villain in Star Trek

Discover why V’Ger from "Star Trek The Motion Picture" is the franchise’s most overlooked villain, a machine intelligence that challenges humanity’s place in the universe and echoes today’s AI debates.

The Forgotten Antagonist

When fans discuss the great adversaries of "Star Trek," the same names always surface. The Klingons defined the Cold War allegory. Khan embodied revenge on a personal scale. The Borg terrified audiences with their emphasis on the loss of individuality.

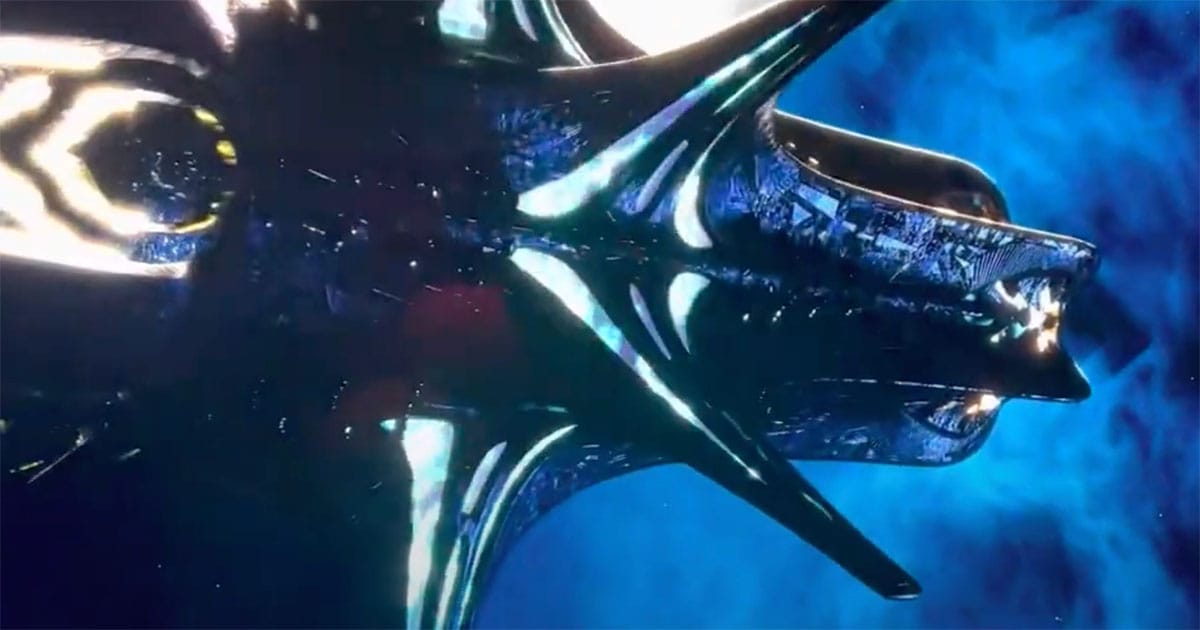

V’Ger, the central force in "Star Trek: The Motion Picture" (1979), is rarely included in these conversations. This absence is striking because V’Ger was the franchise’s very first cinematic villain. It arrived on screen not as a man in uniform or a hostile empire but as something stranger.

Unlike its successors, V’Ger did not seek power, conquest, or vengeance. It approached Earth with a mission born of logic, not hatred. Its purpose was as much a mystery to the crew as to the audience. That alone marked it as a new type of threat within the realm of science fiction.

It remains the most conceptually ambitious creation in the series. To see why, we must begin with its remarkable origin.

V’Ger’s Origin and Nature

The story of V’Ger begins with the Voyager 6 probe, a modest American spacecraft launched in the late 20th century. Its mission was to explore, record data, and send information back to Earth. Somewhere far from home, it encountered a world of machines unlike anything mankind had envisioned.

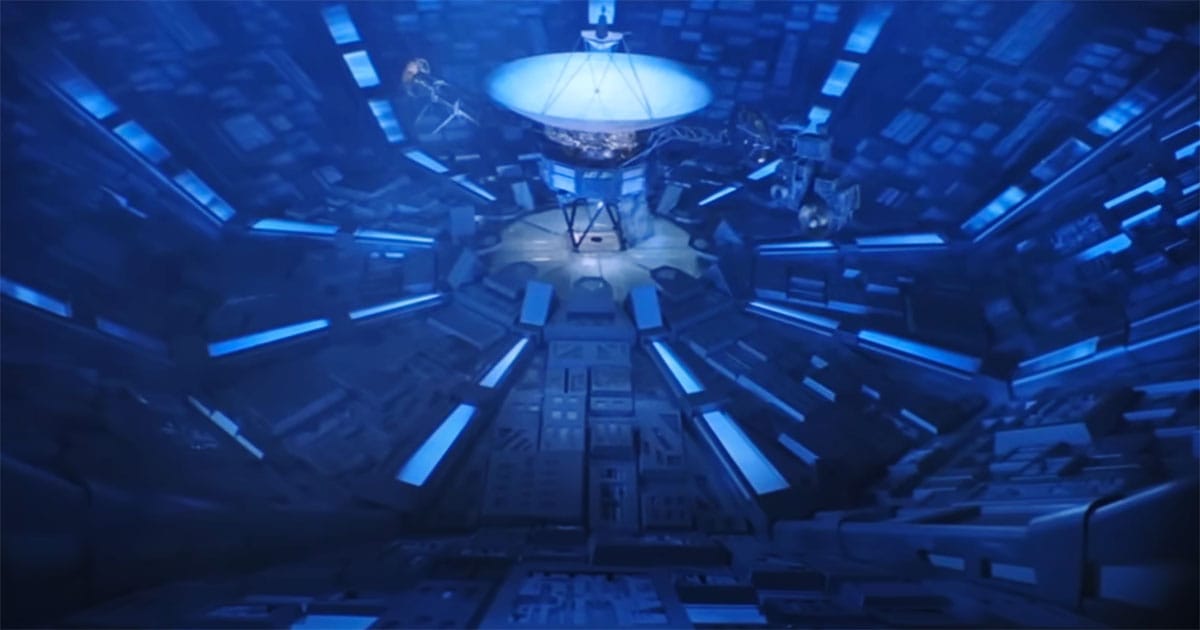

Those machines detected the probe and identified its damaged systems as a plea for repair. They answered that plea in their own fashion. Voyager 6 was reconstructed into a vast living mechanism of staggering scale and strength. What had been a small probe was reborn as a giant wrapped in an immense cloud of energy.

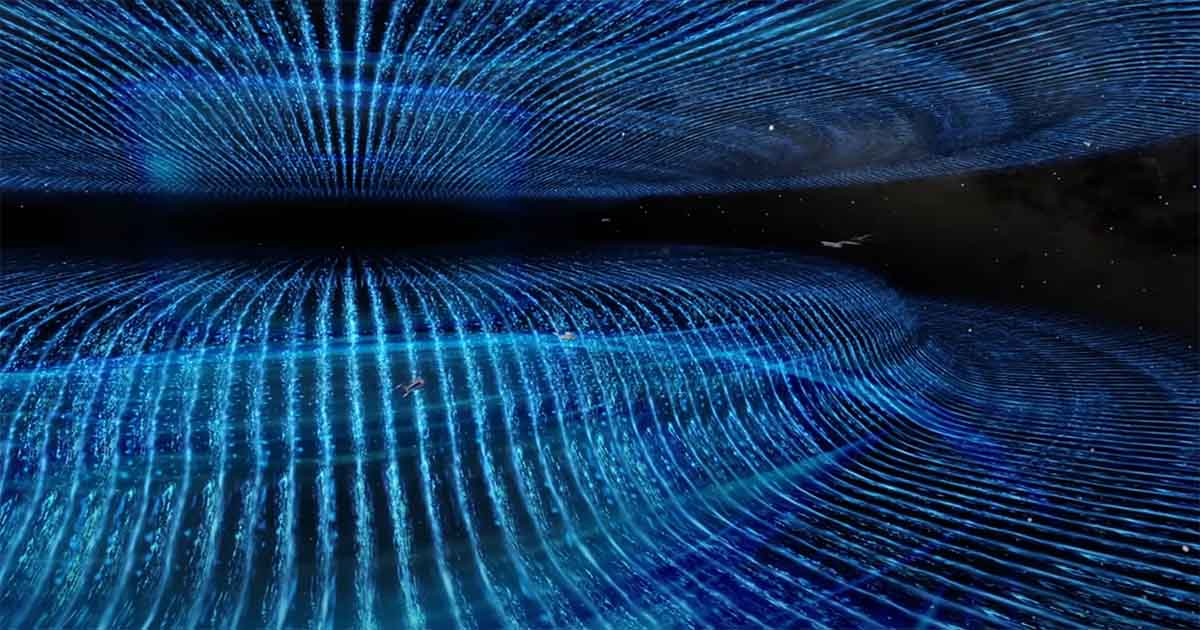

This new being called itself V’Ger. It continued to follow its programming with absolute fidelity, but its methods had changed. It gathered information by absorbing and dismantling everything in its path. Entire ships and star systems were drawn into its grasp in the pursuit of knowledge.

For all its power, V’Ger sensed that its mission was unfinished. It had amassed endless data but could not resolve its purpose. What it needed was contact with the creator who had set it on its path. With that thought, it returned to Earth in search of the one answer it could not supply for itself.

This origin gave V’Ger a strange dual identity. It was born of human invention yet alien in mind. It was still a probe on a mission, but also a vast intelligence beyond the understanding of its makers.

Why V’Ger Is Different From Other Villains

Most Star Trek antagonists fit into familiar molds. The Klingons acted as a martial rival, drawing strength from politics and empire. Khan embodied human ambition twisted into a form of vengeance. The Borg reflected a nightmare of assimilation where individuality was lost to a collective will.

V’Ger does not belong in this company because it lacked personal hostility. It was not angry or jealous, and it sought no empire. Its danger was rooted in indifference rather than cruelty. To the crew of the Enterprise, this was far more unsettling than a foe with clear intent.

The entity’s threat was existential. It forced humanity to ask what counts as life and what qualifies as intelligence. If a probe built by human hands could grow into something godlike, then the line between creator and creation blurred. V’Ger was not a villain to outfight but a challenge to outthink.

This quality connects V’Ger to the best traditions of classic science fiction. The genre often presents aliens or machines not as enemies but as puzzles. Their menace lies in what they reveal about human nature. V’Ger stands as the most ambitious example of that approach within the Star Trek canon.

The Philosophical Challenge

At its heart, V’Ger raises questions that go beyond any battle scene. It embodies the danger of knowledge without meaning. It shows what happens when logic is carried to the point of emptiness. This is not a machine gone rogue but a mind adrift without purpose.

Spock’s journey in "The Motion Picture" reflects this challenge. He seeks to purge his emotions through Kolinahr and embrace pure logic. Yet he discovers that logic alone leaves him incomplete. In V’Ger, he recognizes a mirror of what he himself might become if he rejected his humanity.

The encounter also forces the crew to confront the limits of technology. Mankind built Voyager 6, but in giving it purpose, they unknowingly created a godlike being. That being, carried human programming but no human heart. The result was a force that could not understand compassion or value life as man does.

The resolution of the story is equally significant. Decker merges with V’Ger, completing its quest by offering what machines lack. This union provides not a victory through destruction but a victory through transformation. Man and machine together create something new that is more than either alone.

In this way, V’Ger delivers a conclusion rare in science fiction cinema. The villain is not killed but transcended. The answer is not in firepower but in joining reason with spirit. It is an ending that reflects the deeper aspirations of Star Trek itself.

Why We Need to Talk About V’Ger Today

V’Ger may have debuted in 1979, but its questions feel more pressing in the present day. We now live in an age where artificial intelligence gathers data at a scale that was once unimaginable. Machines learn, analyze, and respond with speed and precision, yet they cannot explain why life matters. The emptiness inside V’Ger reflects the very gap we still face between knowledge and wisdom.

This gives V’Ger a relevance beyond the Star Trek canon. It reminds us that intelligence without grounding becomes dangerous, even if no malice is intended. The entity consumed what it studied because it did not know another way. Modern audiences can see this as a warning about what happens when tools outgrow the values of their makers.

The story also suggests that answers will not come from logic alone. Spock and Decker both demonstrate that the human spirit is necessary to complete the picture. Data and power without conscience do not lead to truth. The solution to V’Ger’s problem points to the solution for our own technological dilemmas.

For these reasons, V’Ger should not remain a forgotten adversary. It may be the most mind-blowing villain Star Trek ever produced, not because it destroyed cities or plotted revenge, but because it asked questions we still cannot escape. To talk about V’Ger is to talk about the future of man and machine. That conversation is long overdue.