Metropolis (1927): When Machines Dream and Men Obey

Explore the towering vision and haunting warnings of Fritz Lang's "Metropolis"—a 1927 silent epic that blends myth, machinery, and morality in one of science fiction’s most enduring masterpieces.

The city in Fritz Lang's "Metropolis" does not sleep. Its towers reach into the clouds, its machines turn without rest, and its people—divided by height and function—move in measured patterns.

Released in 1927, the film imagines a future built on order yet trembling with unrest. It is not only mechanical but symbolic, rich with imagery drawn from myth and machinery alike.

Rather than follow a conventional story, "Metropolis" unfolds like a dream filtered through gears and shadow. Its scenes pulse with repetition, its characters move with a theatrical weight, and every moment seems carved from ambition and unease. The film sees men transformed into tools, cathedrals shaped from steel, and uprising born in the depths below the polished world above.

What "Metropolis" offers is not a prediction but a reflection. It sees the cost of unchecked progress and the tension between soul and system. Few films stare so clearly at the future while echoing the oldest fears of civilization.

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Title | Berlin: Symphony of Metropolis |

| Director | Walter Ruttmann |

| Writer | Carl Mayer, Walter Ruttmann, Karl Freund |

| Actors or actresses | Paul von Hindenburg |

| Rated | Not Rated |

| Runtime | 65 min |

| Box Office | N/A |

| U.S. Release Date | 13 May 1928 |

| Quality Score | 7.6/10 |

Synopsis

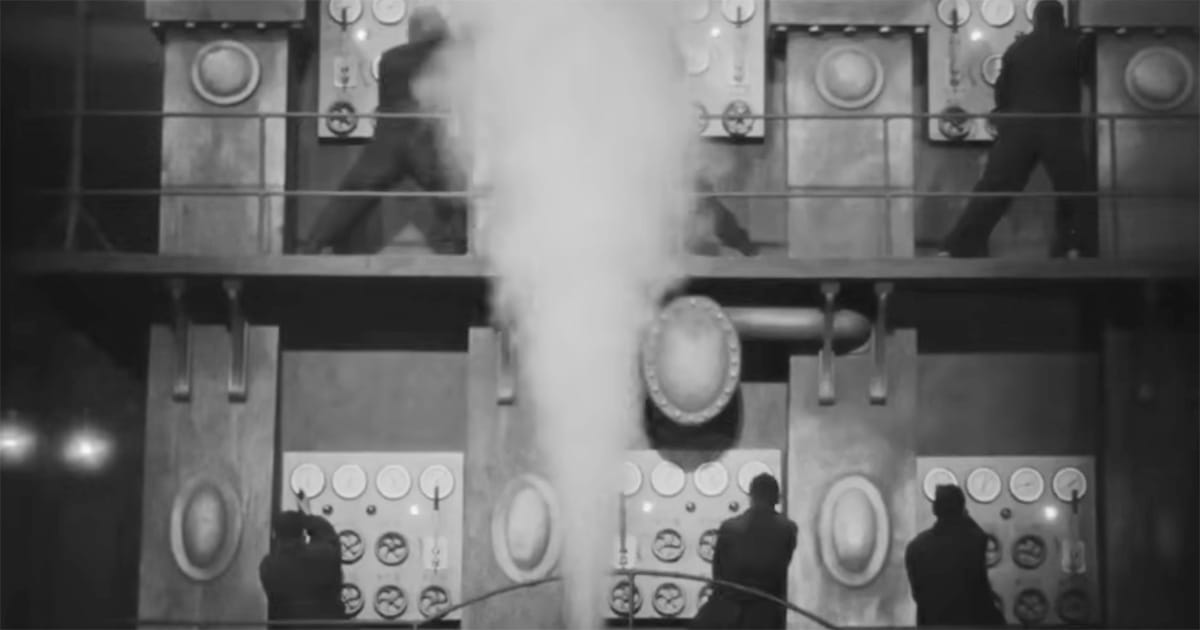

"Metropolis" follows the story of a vast future city divided into two worlds—one of power above, one of labor below. The film opens with a clock striking shift-change as workers march like automatons into the underground machines that sustain the glittering towers above. In contrast, the upper world lives in ease, where Freder, the son of the city’s master, dwells in gardens and pleasure halls, unaware of the toil beneath him.

When Freder discovers the subterranean world, he is horrified and begins a search for justice. Guided by Maria, a saintly figure among the workers, he envisions a path toward unity between head and hands, brokered by the heart. But the balance is soon threatened by a false Maria—an android double sent to stir revolt and chaos. What follows is both riot and revelation, as the city teeters on destruction.

As the towers tremble and the machines groan, "Metropolis" reaches for something more than spectacle. Its story becomes a parable about technology, ambition, and the price of forgetting our shared humanity. The film does not settle for conflict alone—it seeks reconciliation, asking what must be sacrificed for true harmony between those who build the world and those who rule it.

Themes

"Metropolis" is a meditation on power, division, and the human soul under mechanical pressure. It invites not just observation, but reckoning. The film’s towering cityscape is more than a setting—it is a machine made of ambition and fear, driven by hands that no longer remember why they move. Watching it is not passive. One feels drawn into the gears, caught between invention and decay.

One of the film’s most enduring themes is the conflict between technological progress and spiritual purpose. The machines in "Metropolis" are not simply tools. They are idols. They demand sacrifice and shape the rhythm of daily life. The workers toil in cavernous halls, indistinguishable in their uniforms, while above them a different kind of worship plays out—one of pleasure, control, and blindness to consequence. The film asks whether the human soul can survive such a world intact.

The division between the classes is stark and deliberate. "Metropolis" does not soften the contrast between the privileged few and the laboring many. It shows a society stratified not just by wealth, but by elevation—those below ground are kept there, out of sight and out of mind. The upper world walks in gardens and chases amusement. The lower world feeds the heart of the machine. Yet the film does not call for revenge. Instead, it offers a third way—reconciliation through understanding.

Maria, the film’s guiding figure, becomes a symbol for this bridge. Her message is simple—the mediator between head and hands must be the heart. It’s not a technological solution, but a moral one. This idea stands apart from the cold logic of efficiency or the blind fury of revolt. It is not offered as idealism, but necessity. Without the heart, neither the intellect above nor the labor below can sustain civilization.

Lang's visual storytelling reinforces these ideas with precision. From the monumental architecture to the human tide of synchronized workers, every image carries weight. The false Maria—a robot made in her image—embodies the dangers of power without compassion. Her presence disrupts, incites, and nearly destroys. She is what happens when technology mimics the soul without ever possessing it.

Though silent, the film feels loud. The original score, often performed live in early screenings, pushes the emotion to the surface. Even without spoken words, the tension is palpable—the rhythm of pistons, the slow march of workers, the frenzy of collapse. The audience does not simply watch events unfold. They feel the pressure building beneath every scene.

"Metropolis" also explores the temptation to deify progress. The city itself is worshipped by its creator, Joh Fredersen, who sees it as a legacy of order. But the order is brittle. When Freder, his son, descends into the depths, he sees the truth. Order without justice is a form of cruelty. The city may run on steam and steel, but it cannot run without trust.

The film’s enduring power lies in its ability to provoke questions rather than answer them. What is the cost of building a world too complex to understand? What becomes of man when he is forced to imitate the efficiency of his machines? In raising these questions, "Metropolis" becomes more than a cautionary tale—it becomes a mirror for any age willing to look.

The film does not promise utopia. It suggests balance, and warns that imbalance leads to ruin. In that way, "Metropolis" remains uncannily relevant. It speaks not just of its own era, but of ours, where the machine still beckons and man must still choose whether to worship or wield it.

Who would watch this

"Metropolis" holds enduring appeal for viewers with a wide range of interests. Science fiction enthusiasts will find in it the visual DNA of countless later works—from the towering skylines of "Blade Runner" to the robotic archetypes of modern cinema. Those fascinated by the 1920s will see it as a cultural artifact that captures the hopes and anxieties of a world speeding toward industrial perfection. The film bridges the past and the future, offering a window into the fears and dreams that shaped an era.

Viewers drawn to cinematic history will appreciate "Metropolis" for its technical ambition. Fritz Lang’s use of miniatures, layered exposures, and massive sets marked a turning point in visual storytelling. Film students, directors, and cinematographers can study its structure to see how editing, scale, and composition create emotional weight without dialogue. Each scene invites examination, from the symmetry of the machine halls to the expressive close-ups of its characters. It is a silent film that never feels quiet.

Those with an interest in architecture, engineering, or urban design will find "Metropolis" especially compelling. The city itself is a central figure—a vision of vertical ambition and social segregation. Engineers may note the imagined systems of transportation and energy, while architects can study its blend of modernist and Gothic influence. The design speaks not just to function but to control, hierarchy, and spiritual symbolism. It reflects a world built for efficiency, yet haunted by unrest.

"Metropolis" also invites reflection from philosophers and theologians. Its narrative engages with questions of justice, morality, and reconciliation. What kind of society is possible when man forgets his obligations to his fellow man? How should power be wielded in a world where machines mediate every transaction? The film does not answer these questions, but it frames them in a way that lingers long after the final scene.

It is best viewed in a quiet setting, where the viewer can absorb its rhythm without interruption. Screenings with live orchestral accompaniment bring added depth, restoring the cinematic experience as it was once intended. The film does not demand spectacle to impress—it commands attention through design, symbol, and mood.

"Metropolis" rewards those who engage with it earnestly. Whether approached as science fiction, visual art, or social parable, it offers a layered experience that remains relevant nearly a century after its release.