"Solaris" (1972) A Journey into the Human Heart

Tarkovsky’s "Solaris" (1972) transforms space exploration into a study of guilt, memory, and grace, revealing that the greatest unknown lies within the human heart, not among the stars.

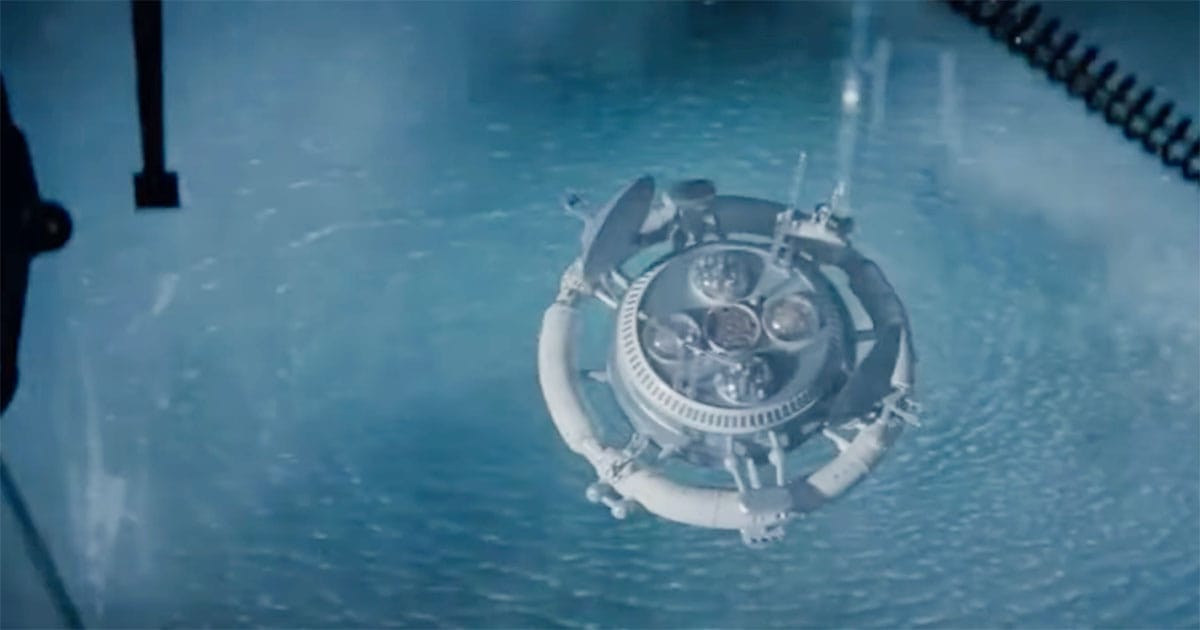

When Andrei Tarkovsky released "Solaris" in 1972, he redefined what a science fiction film could be. Instead of focusing on rockets and cosmic spectacle, he turned his camera inward, toward the landscape of the human soul. The result was a film that dared to question whether man's true frontier was the universe or his own conscience.

Based on the great novel by Polish writer Stanisław Lem, "Solaris" follows a small crew orbiting a living planet that reads human thoughts and brings them to life. The premise is simple, but Tarkovsky uses it as a framework for a profound meditation on guilt, love, and the need for redemption. The planet is not an enemy to be defeated but a mirror that forces man to face what he would rather forget.

At the height of the Cold War and the space race, "Solaris" offered a quiet rebuke to the machinery of progress. Tarkovsky's film asked not how far humanity could go, but whether it deserved to go any farther. Its slow pace and lingering imagery were deliberate acts of resistance against an age infatuated with speed and certainty. What he gave instead was a study of memory and mercy, played out among the stars. The journey outward became a journey home.

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Title | Solaris |

| Director | Andrei Tarkovsky |

| Writer | Andrei Tarkovsky, Fridrikh Gorenshtein |

| Actors or actresses | Donatas Banionis, Natalya Bondarchuk, Jüri Järvet |

| Rated | PG |

| Runtime | 2 h 47 min |

| Box Office | ~10.5 million admissions in the Soviet Union |

| U.S. Release Date | October 6, 1976 |

| Quality Score | 8.6 / 10 |

Synopsis

Kris Kelvin, a psychologist, is sent to a research station orbiting the mysterious planet Solaris. Communication from the crew has grown erratic, and the governing authority demands an investigation.

When Kelvin arrives, he finds the surviving scientists weary and secretive, their minds burdened by fear and confusion. The station itself feels abandoned, haunted by presences that should not exist.

Before long, Kelvin encounters his own apparition — his late wife, Hari, who had died years before. She is alive in every physical sense, though she remembers only what Kelvin remembers of her. The planet, through some unknown process, has drawn this being from his consciousness. It has done the same to others on the station, manifesting physical forms of their most painful memories. Each man is forced to face what he thought was buried forever.

The more Kelvin interacts with Hari, the less he understands his own motives. Love, guilt, and reason tangle until the boundaries between real and imagined collapse. The ocean below, vast and silent, offers no answers. In its endless motion, it reflects the turmoil within those who orbit it. By the end, the mission to study Solaris becomes something else entirely — a confession, a reckoning, and perhaps a plea for grace.

Themes

"Solaris" is often described as a film about space, yet its subject is the mind of man. The planet itself functions as a mirror, responding not to radio signals or probes but to the moral and emotional weight of those who approach it. What it gives back are living images of guilt and desire. Tarkovsky transforms science fiction into moral philosophy, replacing adventure with examination.

The first and most immediate theme is conscience. The scientists aboard the station are not explorers in the heroic sense but penitents. Each faces the living embodiment of a sin or sorrow he cannot erase. The film suggests that humanity's greatest frontier is not interstellar space but the human heart, where memory and responsibility are entwined. The question is not whether we can conquer the unknown, but whether we can live with what we already know about ourselves.

Another theme is the failure of reason. The rational mind, represented by Kelvin's scientific training, cannot comprehend Solaris. The planet does not respond to logic or experiment. It deals in symbols, emotion, and faith. In this way, Tarkovsky implies that science without humility becomes sterile. True understanding demands both intellect and reverence.

Faith itself runs quietly through the film. The ocean's acts of creation echo a kind of divine power, but one that humbles man rather than exalting him. Kelvin's acceptance of Hari's presence becomes a small form of repentance. He cannot change the past, but he can confront it honestly. The film ends not with triumph but with surrender, and that surrender carries a hint of grace.

Tarkovsky also explores the limits of human connection. The characters, isolated in orbit, discover that even love can become a form of self-deception. Hari, though born of memory, develops her own will and despair. Her tragedy lies in her awareness that she is both real and unreal. Through her, Tarkovsky asks whether love is an act of possession or of mercy.

Finally, "Solaris" rejects the mechanical optimism of much Western science fiction. Where American films of the same era celebrated technology and conquest, Tarkovsky returned to the elemental and the spiritual. His space station is cold and metallic, but his Earth is warm and alive. The contrast reminds the viewer that progress without reflection leads only to loneliness. The true unknown is not the universe beyond the stars but the soul that looks up at them.

Who Will Watch This

"Solaris" was not made for those who watch science fiction for speed or spectacle. It speaks to the viewer who values thought over thrill, and who prefers to listen rather than be dazzled. The film rewards patience, inviting reflection on memory, guilt, and the mystery of being human. Its beauty lies not in its effects, but in its honesty.

The ideal viewer is one who reads Lem, Asimov, or Clarke and looks beyond their machines to the moral questions beneath. He finds satisfaction in long silences and unresolved questions. He accepts that not every mystery must be solved, and that wonder often comes with discomfort. For him, "Solaris" is less a story and more an experience — an examination of conscience disguised as a journey through space.

Younger audiences raised on digital spectacle may find its pace slow, but those who give it time will discover a work of quiet revelation. Its images linger long after the credits fade, like memories that will not let go. In the end, "Solaris" asks each man to consider his own ghosts and what he might do if they came back to him. It remains one of the few films brave enough to say that understanding ourselves may be the hardest exploration of all.