The 21 Greatest Science Fiction Films Never Made

Twenty-one legendary sci-fi movies never made. Lost epics, canceled sequels, and forgotten visions that still haunt Hollywood’s imagination.

Hollywood's Phantom Zone

Every film buff knows the stories about Hollywood blockbusters that shouldn't have worked but somehow did. Star Wars nearly went broke before its first screening. Blade Runner baffled critics and studio execs alike. But the real treasures of science fiction cinema are the ones that never left the launchpad — the films trapped forever in what might be called Hollywood's phantom zone.

It is a strange place, this development purgatory. Here float the dreams of directors who thought bigger than budgets, writers who dared to imagine the impossible, and producers who believed a little too hard that audiences would sit through a fourteen-hour metaphysical odyssey about sandworms.

Every few years, a new filmmaker wanders into this mist, convinced he can tame the same unfilmable beasts that devoured his predecessors. Usually, he can't. Sometimes, he comes close enough to change the course of science fiction anyway.

The truth is, the genre has always lived at the edge of sanity and solvency. The best ideas tend to be the most dangerous. Alejandro Jodorowsky tried to turn Dune into a psychedelic gospel. Guillermo del Toro thought he could bring H. P. Lovecraft's cold cosmos to the multiplex. David Fincher wanted to make a movie about discovery with no villain, no explosions, and no toys to sell. Each of them failed — spectacularly — but their failures still resonate through the movies that were made.

The unmade science fiction film is more than a curiosity. It is a reflection of what the industry fears most: risk, ambiguity, and imagination that refuse to fit in a two-hour window.

These lost projects remind us that creativity isn't always rewarded with a greenlight, and that sometimes the most influential stories are the ones we only get to picture in our minds.

So buckle in. Ahead lies a guided tour through Hollywood's haunted archives—a place where Salvador Dalí still waits for his close-up, Tom Cruise never reaches Antarctica, and a sentient computer named Mike never gets his revolution. Welcome to the phantom zone, where the movies that never were might just be the best ones of all.

21 Lost Science Fiction Films That Still Haunt Hollywood

| Title | Director / Creator | Years in Development | Key Detail | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dune | Alejandro Jodorowsky | 1974–1976 | 10+ hour spiritual epic with Dalí, Welles, and Jagger | Canceled, influenced Alien and Star Wars |

| At the Mountains of Madness | Guillermo del Toro | 2006–2012 | Lovecraft adaptation, Cruise attached, Cameron producing | Shelved after studio rejected R rating |

| Rendezvous with Rama | David Fincher | 2001–2011 | Clarke adaptation, Freeman producing | Abandoned; revived by Denis Villeneuve in 2021 |

| Childhood’s End | Stanley Kubrick | 1960s | Clarke novel about transcendence | Abandoned; rights held elsewhere |

| Alien 3 | William Gibson (screenwriter) | 1987–1988 | Cold War-style Alien sequel | Replaced by Fincher version; adapted as comic |

| Alien 5 (Awakening) | Neill Blomkamp | 2015–2017 | Direct sequel to Aliens ignoring later films | Canceled in favor of Prometheus prequels |

| Rogue Squadron | Patty Jenkins | 2020–Present | Starfighter adventure inspired by classic Star Wars lore | Indefinitely shelved by Lucasfilm |

| District 10 | Neill Blomkamp | 2021–Present | Sequel to District 9, focused on corruption and power | In limbo; never entered production |

| Star Trek | Quentin Tarantino | 2017–2020 | R-rated 1930s gangster-inspired Trek concept | Abandoned when Tarantino retired project |

| I, Robot | Harlan Ellison | 1977–1980s | Asimov adaptation written as a noir mystery | Unproduced; published as Illustrated Screenplay |

| Neuromancer | Various (Natali, Cunningham, etc.) | 1990s–2020s | Gibson’s cyberpunk novel | Multiple failed attempts; Apple TV+ series in development |

| Stranger in a Strange Land | Various / SyFy | 1990s–2016 | Heinlein’s philosophical novel | Announced by SyFy; quietly canceled |

| The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress | Tim Minear / Bryan Singer | 2005–2015 | Lunar revolution with sentient AI | Abandoned amid production and legal issues |

| Ringworld | Various (incl. Alan Taylor) | 1970s–2017 | Vast artificial world by Larry Niven | Amazon pilot canceled; rights inactive |

| Halo | Neill Blomkamp / Peter Jackson | 2005–2006 | Live-action game adaptation | Canceled over financial dispute; led to District 9 |

| The Diplomat | Howard Hawks / William Faulkner | 1951–1952 | Alien envoy satire set in Washington | Never produced; only conceptual notes survive |

| War of the Worlds | Ray Harryhausen | Early 1950s | Victorian setting, tentacled Martians | Canceled; Pál’s modern version made instead |

| The Elementals | Ray Harryhausen | 1970s | Mythic story of warring elemental spirits | Abandoned due to budget concerns |

| Calling All Robots | Michael Dougherty | 2008–2011 | Animated mecha adventure | Canceled after Mars Needs Moms failure |

| Meltdown (The Prometheus Crisis) | John Carpenter | 1980s | Nuclear-reactor thriller | Never greenlit; script remains unpublished |

| Ronnie Rocket | David Lynch | 1977–1983 | Surreal electric-noir sci-fi | Unproduced; ideas resurfaced in later works |

The Unfilmable Epics

Hollywood has never been short on ambition. The difference between a dreamer and a madman is usually about fifty million dollars — and nowhere is that more evident than in the long, dusty trail of unmade science fiction epics.

These were the projects that aimed for the stars, terrified accountants, and left concept artists with nothing but heartbreak and storyboards.

Alejandro Jodorowsky's "Dune" (1974–1976)

Before Star Wars and before Alien, there was Jodorowsky's Dune — a film that never existed but somehow managed to change everything. The Chilean-French director Alejandro Jodorowsky envisioned it as a "prophet-making machine," a spiritual bomb that would awaken humanity. He wasn't exaggerating.

He planned a 10- to 14-hour movie starring Salvador Dalí as the Emperor (for $100,000 an hour), Orson Welles as Baron Harkonnen, and Mick Jagger as Feyd-Rautha. Pink Floyd would handle the soundtrack. Moebius, H.R. Giger, and Chris Foss were tasked with designing worlds that made most 1970s sci-fi look like a high school play.

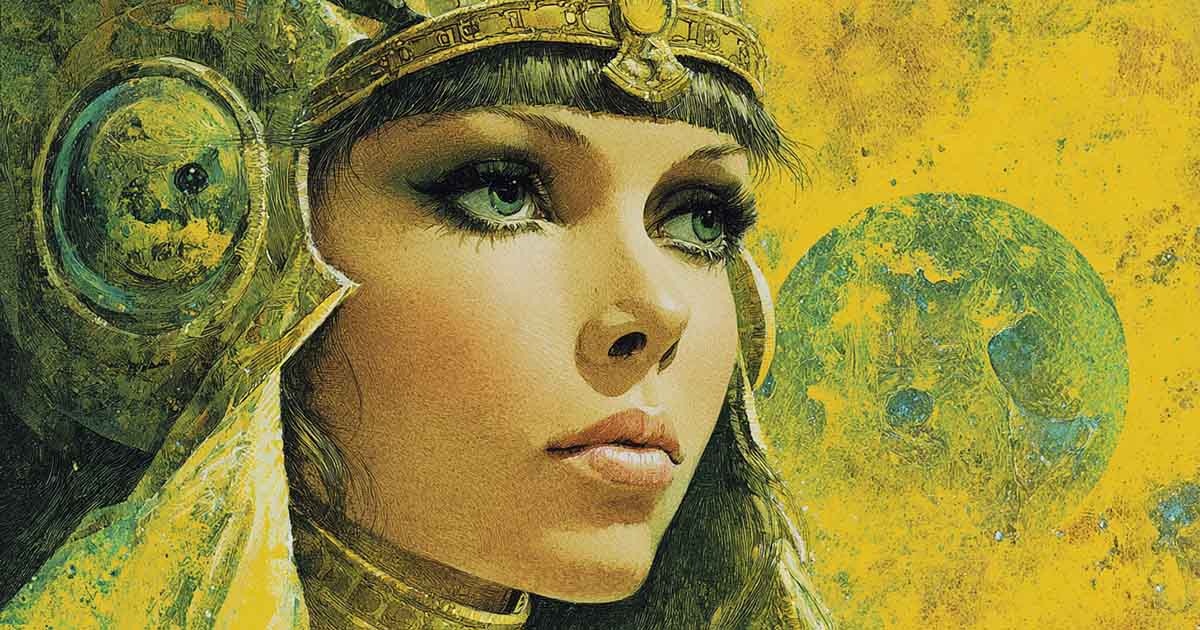

Concept art from Jodorowsky's Dune via Sony Classics.

No studio would touch it. The budget ballooned before cameras ever rolled. Jodorowsky refused to cut the runtime or compromise his surreal vision.

By 1976, the project collapsed, but not before its pre-production art made the rounds in Hollywood. Those storyboards directly inspired Alien and helped shape the visual DNA of Star Wars and Blade Runner.

In a sense, Jodorowsky's Dune did get made — it just took forty years and a dozen other directors to do it. The documentary, released decades later, confirmed what fans already suspected: sometimes, the most important movie is the one you never get to see.

Guillermo del Toro's "At the Mountains of Madness" (2006–2012)

Guillermo del Toro is one of those filmmakers who builds worlds, not just movies.

For years, he carried H. P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness in his back pocket — a doomed Antarctic expedition story drenched in cosmic dread. It was the perfect match of artist and author.

By 2010, Universal Pictures had signed on. James Cameron was producing. Tom Cruise was ready to star. Industrial Light & Magic was lined up for effects. But the studio flinched. Del Toro wanted an R rating and a $150 million budget. Universal wanted a PG-13 and a happy ending. The script had neither. Then Prometheus came along, covering similar territory — scientists exploring the ruins of a creator race — and del Toro's dream went cold overnight.

He never really gave up. A few years ago, he shared test footage of an early creature sequence, all writhing tendrils and madness rendered in cold CGI.

In 2022, he announced that he might return to the story in stop-motion form — a smaller, weirder version free from blockbuster expectations. That might actually suit the tale better. Lovecraft never needed a giant screen; he needed imagination. Del Toro has plenty of that to spare.

David Fincher's "Rendezvous with Rama" (2001–2011)

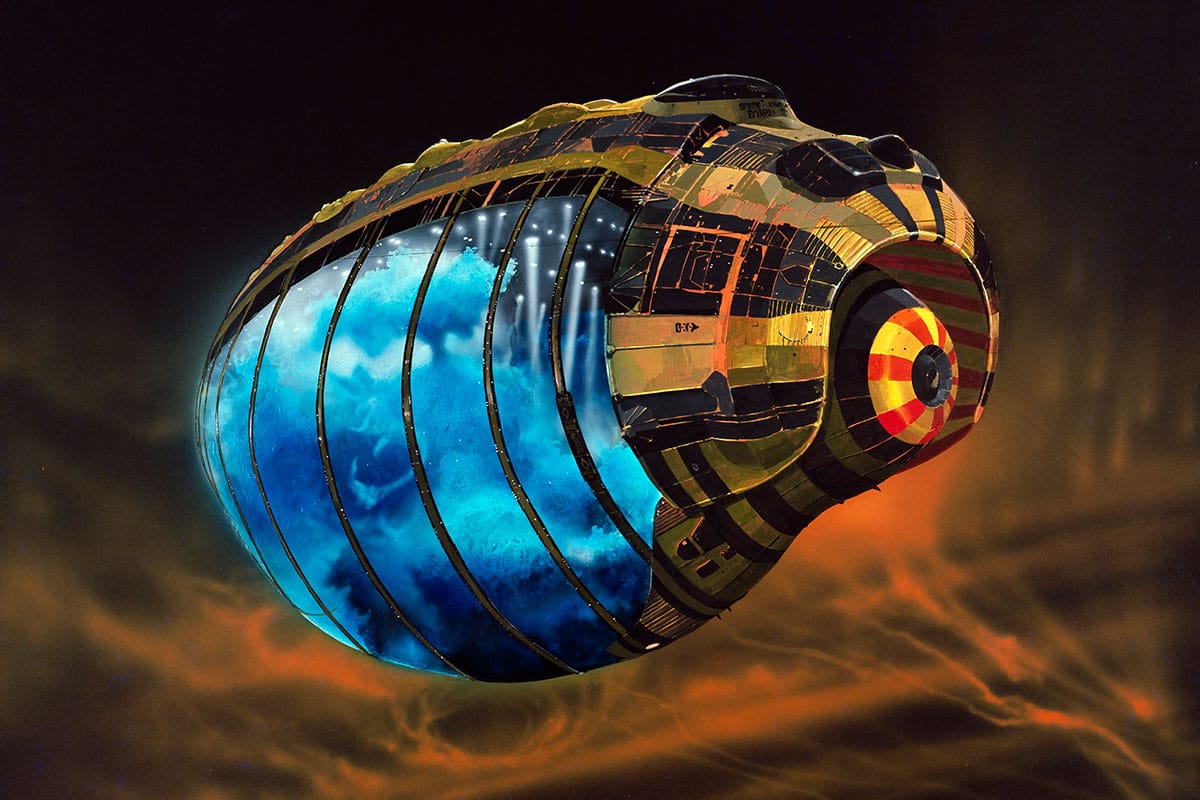

Arthur C. Clarke's Rendezvous with Rama is not an easy sell. No villain. No chase. No explosion — just astronauts quietly exploring a colossal alien cylinder that drifts into the solar system.

For director David Fincher and producer Morgan Freeman, that was precisely the appeal.

Fincher spent years trying to make it work. The story's mystery and cosmic scale were perfect for his meticulous style, but Hollywood couldn't figure out how to market a movie about wonder instead of war. As Fincher put it, it was "a gigantic, expensive movie that didn't have any toys." By 2008, he admitted defeat, and the project went dark.

Then, in a twist that Clarke himself might have appreciated, the idea was reborn. In 2021, Denis Villeneuve — fresh from his triumph with Dune —picked up Rama with Freeman still producing.

The baton had passed to a new generation of dreamers. Whether it happens or not, the attempt alone proves something about science fiction's stubborn optimism. In this business, no idea ever really dies; it just goes into hibernation until the right mind awakens it.

Stanley Kubrick's "Childhood’s End" (1960s)

Before 2001: A Space Odyssey, Stanley Kubrick had his eye on another Arthur C. Clarke novel: Childhood's End. It tells the story of a peaceful alien invasion that ends humanity — not through destruction, but through transcendence.

The aliens, known as the Overlords, guide mankind toward a final evolutionary leap into a collective consciousness. It's brilliant, bleak, and a little too philosophical for a matinee crowd.

Kubrick loved it but could not secure the rights. Instead, he and Clarke developed an original story that borrowed its cosmic tone and metaphysical questions. That collaboration became 2001. In a strange way, Childhood's End was sacrificed so that another masterpiece could live.

Years later, SyFy turned it into a miniseries, but the magic was gone. Kubrick understood that stories like this were not meant to explain the unknown. They were meant to make you feel small, awed, and slightly terrified by the scale of existence. That is a hard sell in an era obsessed with superheroes, but it is still the heart of great science fiction.

Unfilmable

These were the unfilmable epics — too strange, too big, or too pure for Hollywood to handle. Yet, even as unfinished dreams, they had a profound influence on everything that followed. Their storyboards and half-written scripts became the compost from which modern science fiction grew. The movies were never made, but their shadows are everywhere.

Ghosts in the Machine

Every major science fiction franchise eventually becomes haunted by its own success.

Once a story captures the imagination, every studio executive within a hundred miles starts looking for ways to stretch it further, like a rubber band that refuses to snap.

Sequels, prequels, spin-offs — sometimes they make it to the screen, sometimes they vanish into a development void. What remains are the ghosts of movies that almost were, phantom blueprints for universes that could have been bigger, stranger, or maybe just better.

Quentin Tarantino's "Star Trek" (2017–2020)

For a brief, gleaming moment, Star Trek fans imagined a version of the Federation that spoke in Tarantino dialogue and bled like one of his gangsters. In 2017, the director pitched Paramount a boldly unorthodox idea: a hard-R Star Trek film inspired by a 1968 episode, "A Piece of the Action," in which the Enterprise crew encounters a planet that has modeled its society after 1920s gangsters. Tarantino called it "Pulp Fiction in space," and J. J. Abrams signed on to produce.

The project moved further than most curiosities. Tarantino met with writers, including The Revenant's Mark L. Smith, and Paramount treated it as an active development track alongside its mainline franchise. Then came the director's vow to retire after ten films and the studio's shift toward safer PG-13 projects. By 2020, Tarantino had stepped away, leaving behind a script that few insiders have read and everyone seems eager to describe.

What might it have looked like? Probably not what the purists feared. Tarantino once said he loved the "philosophical optimism" of classic Trek and wanted to push it through the lens of adult storytelling rather than irony. Still, the image of Kirk trading quotes with gangsters under neon starlight was too much for Paramount's nerves. The project now floats among the studio's deepest ghosts — a reminder that even the most mainstream franchises sometimes attract the wildest dreamers.

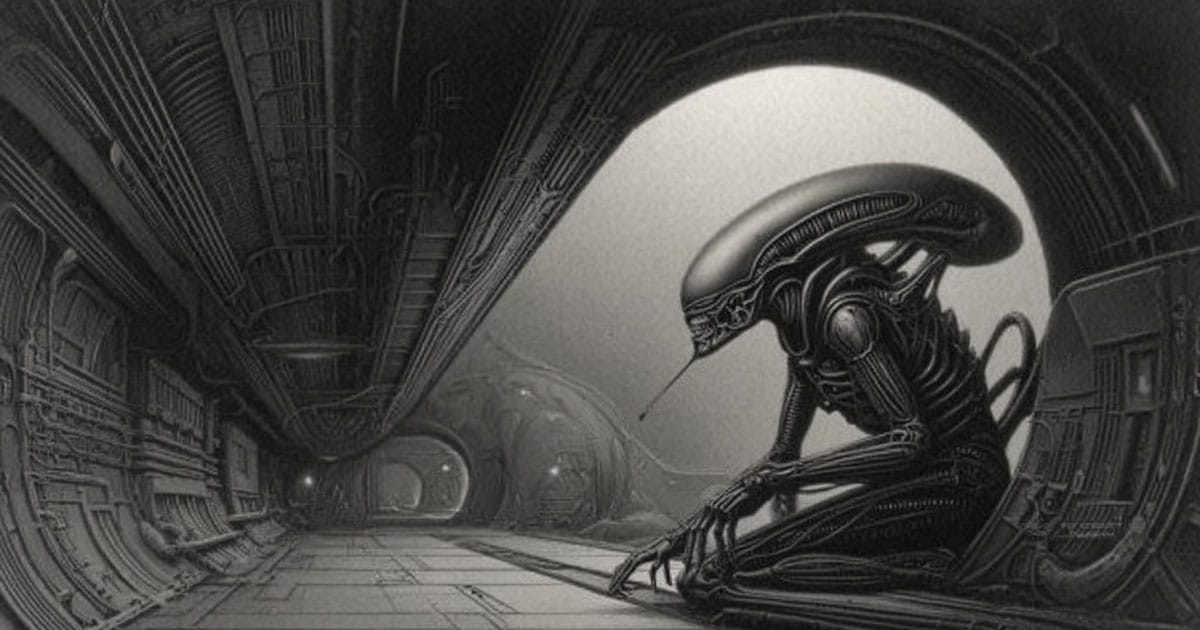

William Gibson's "Alien 3" (1987–1988)

When 20th Century Fox called cyberpunk legend William Gibson to write Alien 3, the idea was to take the series back to its Cold War paranoia roots.

Gibson's script imagined a divided human future, where the "Union of Progressive Peoples" and a corporate military complex fought over bio-weaponized xenomorph DNA. Ripley was in a coma for most of it. Hicks and Bishop led the action. It was The Thing meets The Manchurian Candidate — a sequel more about politics and fear than jump scares.

Fox executives were unsure how to respond. They wanted monsters, not metaphors. The draft was shelved, rewritten half a dozen times, and eventually replaced by David Fincher's moody prison-planet version in 1992.

Gibson's story gathered dust for decades until it was finally adapted as a comic and an audio drama. Listening to it now, you can almost feel the movie breathing under the surface — a cold, metallic dream from an alternate 1980s where science fiction kept its edge and its brains intact.

Neill Blomkamp's "Alien 5" (2015–2017)

Fast-forward three decades, and another dreamer came knocking. After District 9, Neill Blomkamp was the darling of serious sci-fi — a director who could mix hardware and heartbreak.

His pitch for Alien 5 was simple: pretend Alien 3 and Resurrection never happened. Bring back Ripley, Hicks, and Newt. Give fans the ending they never got.

He released concept art online — aged Ripley in a pressure suit, Hicks scarred but alive, the derelict ship half-buried in acid fog — and the internet went wild.

For a moment, it looked like the xenomorphs would finally come home. Then Ridley Scott stepped in. The studio chose his Prometheus prequels instead. Blomkamp's film was quietly killed before a frame was shot.

It is one of modern cinema's crueler what-ifs. Every so often, the director teases the designs on social media, and the fan base groans in unison. The lesson? Even the fiercest creatures in movie history cannot survive a scheduling conflict.

Patty Jenkins' "Rogue Squadron" (2020–Present)

When Disney announced Rogue Squadron, it sounded like the perfect marriage of nostalgia and new energy. Patty Jenkins — fresh off Wonder Woman — promised a "high-speed, high-heart" story inspired by her father, an Air Force pilot. It was supposed to bring Star Wars back to its roots: X-wings, camaraderie, heroism. For longtime fans, it was a breath of oxygen after years of Jedi family drama.

Then the turbulence began. Script rewrites, internal shake-ups, and the gravitational pull of a dozen other Lucasfilm projects sent the fighter squadron spinning off radar.

The release date slipped from 2023 to "TBD," and Jenkins moved on to other work. For now, Rogue Squadron is parked in the hangar — a reminder that even the galaxy's most profitable franchise can stall when it forgets to check its own coordinates.

Neill Blomkamp's "District 10" (2021–Present)

Of all the ghosts in this gallery, District 10 may be the most self-inflicted. Blomkamp created one of the most original science fiction films of the twenty-first century with District 9, then spent years circling its potential sequel. He promised it would confront government corruption and race in a new way, perhaps shifting the story from Johannesburg to the United States. Every time he mentions it, hope flickers.

And every time, he changes his mind. Blomkamp admits he does not want to repeat himself, and that is probably wise. Still, there is something poignant about a filmmaker haunted by his own masterpiece — like a scientist afraid to open the lab door again because the last experiment worked too well.

Ghosts

The franchise ghost is a uniquely modern phenomenon. These films were not crushed by impossible budgets or artistic hubris. They were smothered by success, trapped in the gravity of expectations built over decades. Yet their absence leaves a kind of resonance, a hum beneath the culture. Fans keep their memories alive with concept art, comics, and podcasts.

The studios may call it development hell, but for the rest of us, it is something closer to purgatory—a waiting room between imagination and commerce where the machines never sleep, and the ghosts of what might have been keep whispering through the circuits.

From Page to Phantom Screen

Science fiction writers dream bigger than the movies ever can. Their words conjure galaxies, philosophies, and futures that don't fit neatly into two hours and three acts.

Hollywood has tried to bridge that gap for decades. Sometimes it succeeds. Most of the time, the bridge collapses under the weight of imagination. The following stories illustrate what happens when great books encounter unyielding publishers.

Harlan Ellison's "I, Robot"

Harlan Ellison's collaboration with Isaac Asimov should have been the ultimate meeting of minds.

Asimov provided the cool rationalism — the Three Laws of Robotics. Ellison brought the passion, paranoia, and punch of a screenwriter who could make a machine sound human and a human sound like a machine. His 1977 screenplay turned Asimov's anthology into a single story about a psychologist investigating a robot-driven mystery. It was sharp, adult, and ahead of its time.

The problem was Hollywood. The studios wanted something lighter, maybe with more laser fights and fewer existential questions. Ellison didn't compromise, and the project died on the vine. He published the script as I, Robot: The Illustrated Screenplay, complete with production notes and storyboards.

Reading it now, you can feel the movie that might have been — Blade Runner before Blade Runner, a mix of ethics, fear, and melancholy that would have fit perfectly in the anxious late seventies.

Ellison's version never made it to the screen, but it became a ghost blueprint. When Alex Proyas finally made I, Robot in 2004, he used Asimov's title and little else. The sleek summer blockbuster was the antithesis of Ellison's grim warning. His unmade version remains the more faithful adaptation — the one that understood robots as a mirror, not a menace.

William Gibson's "Neuromancer"

Few books have predicted their own failure to be filmed as accurately as Neuromancer.

William Gibson's 1984 novel coined the term "cyberspace" and foresaw a wired world years before the web existed. But Gibson's writing — dense, poetic, disorienting — was not built for screenplays. Directors from Vincenzo Natali to Chris Cunningham attempted to translate his cold vision of a future dominated by hackers, data thieves, and artificial consciousness. Each ran into the same problem: how do you film a hallucination without losing the mystery?

By the 2000s, the project had developed a reputation as cursed. The visual style had already been absorbed by movies like The Matrix and Ghost in the Shell, making Gibson's original vision seem redundant to the very films it inspired.

Still, the property refuses to die. Apple TV+ is now developing a series version, which might finally have the scope to capture Gibson's layered world—a realm where the sky is "the color of television tuned to a dead channel" and the heroes are broken, brilliant outlaws.

A Neuromancer adaptation may never feel new again, but that's the irony. Gibson wrote about a world where everything is recycled, copied, and commodified. Every failed attempt proves he was right.

Robert Heinlein's "Stranger in a Strange Land"

In the sixties, Stranger in a Strange Land was revolutionary — part gospel, part satire, part counterculture manifesto.

Heinlein's story of Valentine Michael Smith, the human raised by Martians who returns to Earth preaching free love and psychic unity, was a best-seller and a scandal. It gave the English language the word "grok," meaning deep understanding, and inspired communes, sermons, and late-night dorm debates.

A film version, though, has always been a minefield. The book's theology of self-deification and its open talk about sex and society make studio executives sweat. Actor Tom Hanks once held the rights in the 1990s, hoping to produce a faithful adaptation, but even his clout could not navigate the minefield. In 2016, Syfy announced a series with Paramount Television, only to let it fade without explanation.

The real obstacle is not content — it's tone. Heinlein wrote ideas, not scenes. The book shifts from science fiction to sermon, from Martian philosophy to Earthly chaos. Translating that is like trying to film a dream that lectures you halfway through. The story survives best where it started — in the imagination.

"The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress"

If Stranger in a Strange Land was Heinlein's sermon, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress was his manifesto.

Written in 1966, it is a political thriller disguised as hard sci-fi — a lunar penal colony fighting for independence with the help of a sentient computer named Mike. It is the American Revolution played out on the moon, with libertarian ideals and cold logic as weapons.

It should have been cinematic, rebellion, humor, and a built-in special effect — low gravity. Yet every attempt to film it has sputtered. Firefly writer Tim Minear wrote a faithful script in 2005 that went nowhere. A decade later, 20th Century Fox tried again under the title Uprising, with Bryan Singer attached to direct. That version died after the director's personal scandals made him untouchable in Hollywood.

Heinlein's narrative is a machine of logic and debate, not emotion. What works on the page — discussions of revolution, self-governance, and the rights of man — plays like a civics lecture on screen. Still, it remains one of the few unmade films that feels inevitable. Sooner or later, some filmmaker will get tired of superheroes and rediscover Heinlein's lunar patriots.

Larry Niven's "Ringworld"

Larry Niven's Ringworld is one of the grandest ideas ever printed. A man-made ring circling a star, so vast it could hold three million Earths.

It is science fiction as architecture. The challenge for filmmakers has always been matching that scale. The book is primarily an exploration — a handful of humans and aliens wandering through impossible landscapes as they try to understand who built them. There's no villain, no romance to speak of, and no clear ending, just awe.

Hollywood loves awe until it gets the bill. A feature version has been "in development" since the 1970s. A Syfy miniseries came close in 2004, then again in 2013. Amazon picked it up in 2017, with Game of Thrones director Alan Taylor attached to the pilot, but the project stalled due to rights and budget issues.

To make matters worse, video game fans now associate the giant orbital ring with Halo, even though Niven invented the idea first. That makes any film version look derivative by accident. For now, Ringworld remains the largest movie never made — a reminder that imagination has no scale limit, but budgets do.

Books Not on Film

From Asimov's reason to Gibson's rebellion, Heinlein's theology to Niven's geometry, these unmade adaptations chart the limits of what studios can handle. They reveal a truth older than Hollywood itself: it is easier to build a rocket than to bottle a big idea.

These projects tell the same story in different costumes. Big ideas draw readers in and scare studios off. Dialogue that sings in print goes flat at 24 frames per second. Still, the influence leaks out. Ellison's bruising seriousness about robots. Gibson's style grafted onto a dozen neon futures. Heinlein's questions about liberty and faith never stop poking the culture. Even stalled, these adaptations shape what gets made next.

If the unfilmable epic is about scale, this chapter is about philosophy. Translate a vision, and you might lose it. Refuse to translate, and you risk losing the audience. That tension is the phantom screen — bright, tempting, and just out of reach.

The Other Lost Worlds

Not every phantom project began with a best-selling novel or a billion-dollar franchise. Some started with a blank page and too much imagination.

These are the forgotten originals — the films born from bold concepts, new media, or simply directors who reached beyond what studios could understand.

They are the other lost worlds, each undone by the same mixture of ambition and bad timing.

Neill Blomkamp's "Halo" (2005–2006)

Few failed productions changed science fiction more profoundly than Halo.

In 2005, Microsoft wanted to turn its record-breaking video game into a cinematic juggernaut. They hired Peter Jackson to produce and a young Neill Blomkamp — then known for commercials and short films — to direct. The plan promised a gritty, live-action vision of interstellar warfare.

The deal blew up before cameras rolled. Microsoft demanded $10 million upfront, 15 percent of box office receipts, and final creative control, while refusing to contribute to the production budget. Fox and Universal, who had agreed to co-finance, walked away in 2006. The dream of Spartans and Covenant armies collapsed overnight.

Yet, from that wreckage came something extraordinary. Blomkamp used the same art department, props, and creative team to produce District 9. What had begun as a corporate property turned into one of the most original science fiction films of the century — political, personal, and utterly distinct.

Halo's failure was not an ending; it was a transformation. Sometimes, when the machine breaks, art slips through the gears.

Howard Hawks and William Faulkner's "The Diplomat" (1951–1952)

In the early fifties, two American giants — director Howard Hawks and writer William Faulkner — briefly joined forces to create a science fiction satire titled The Diplomat. The premise reportedly followed an alien envoy visiting Washington, D.C., only to find humanity more absurd than any extraterrestrial species. Think The Day the Earth Stood Still rewritten by a Southern novelist with a whiskey glass in hand.

Hawks and Faulkner were an unlikely but proven duo. They had already collaborated on To Have and Have Not and The Big Sleep, where Faulkner's sharp dialogue matched Hawks's confident visual storytelling. But The Diplomat never made it past the idea stage. No studio was eager to bankroll a cerebral comedy about first contact during the Cold War. The script, if it ever existed, vanished into the pile of unproduced Faulkner screenplays.

The irony is that both men were right for the job. Hawks understood banter and tension. Faulkner understood pride and delusion. Together, they might have made a film that dissected humanity's political vanity long before Dr. Strangelove. Instead, The Diplomat remains a ghost of a movie that could have made America laugh at itself during the decade it least wanted to.

The Lost Worlds of Ray Harryhausen (1950s–1970s)

Ray Harryhausen made monsters move long before digital effects existed. He brought skeletons to life in Jason and the Argonauts and giant octopi to the Golden Gate Bridge in It Came from Beneath the Sea. But even he could not animate a green light from the studios.

Many of his dream projects were too ambitious, too handmade, or too costly for their time.

His most famous unrealized film was War of the Worlds. In the early 1950s, Harryhausen pitched a faithful adaptation of H. G. Wells's novel, set in Victorian London and featuring the Martians as tentacled horrors rather than sleek saucers. He built models and test footage, but investors chose George Pál's modernized version instead. Later, Harryhausen developed The Elementals, a mythic tale of warring spirits battling across ancient ruins, only to see it die in pre-production.

In the end, Harryhausen's unmade films became part of his myth. They remind us that the craftsman's imagination exceeded his era's technology. Every stop-motion creature he did complete carries a trace of the ones he never could.

Disney's "Calling All Robots" (2008–2011)

In the late 2000s, Walt Disney Pictures teamed with Robert Zemeckis's ImageMovers Digital to create a motion-capture animated feature called Calling All Robots. Directed by Michael Dougherty (Trick' r Treat), it told the story of a boy who joins Earth's mech defense program to fight giant monsters — only to uncover that the war is staged for profit by a corrupt general. It was pulp adventure with a moral edge.

Production was well underway when Mars Needs Moms (2011) flopped so catastrophically that Disney shut down the entire studio. The collateral damage took Calling All Robots with it. The cancellation was final, but its DNA lived on: two years later, Pacific Rim hit theaters with strikingly similar imagery and themes.

The film's concept art — sleek robots, glowing cities, Cold War color palettes — circulated online for years. Like many lost projects, it didn't disappear; it simply mutated. Its influence reemerged through other creators, proving that even unbuilt worlds leave shadows on the wall.

John Carpenter's "Meltdown (The Prometheus Crisis)" (1980s)

After The Thing and Escape from New York, John Carpenter wanted to make a nuclear thriller. Meltdown (The Prometheus Crisis) follows a scientist trapped in a reactor complex as a chain reaction threatens to consume the planet. The script blended the claustrophobic tension of Alien with the moral panic of Dr. Strangelove.

The project languished through development in the 1980s, but no studio was willing to touch nuclear disaster material. By then, audiences had already absorbed The China Syndrome and real-world scares like Chernobyl.

Carpenter's vision — a mix of horror, heroism, and atomic anxiety — was shelved. The script circulates quietly online, a relic from a time when filmmakers still thought nuclear war could be stopped by one good man and a wrench.

David Lynch's "Ronnie Rocket" (1977–1983)

Before making Blue Velvet or Twin Peaks, David Lynch attempted to create a surrealist sci-fi mystery film called Ronnie Rocket.

It followed an electrically charged dwarf who dreams of becoming a rock star while a detective explores a dimension ruled by industrial noise. It was strange even for Lynch — part noir, part nightmare, part rock opera.

For six years, he shopped the script around town. Every studio passed. Some said it was too weird; others simply did not understand it. Lynch moved on to The Elephant Man, Dune, and eventually Eraserhead's spiritual successors on television. Yet he still calls Ronnie Rocket his lost love.

The film's imagery — a city powered by electricity and madness — would resurface throughout his later work. Like the other lost worlds of this section, Ronnie Rocket may never have existed, but it continues to haunt everything that followed.

The Lost

These projects form the genre's outer rim — the experiments, oddities, and near-misses that stretch beyond adaptation or franchise logic. They remind us that science fiction isn't built only from success stories. It is built from the wreckage of imagination itself, the blueprint lines of films that never quite solidified into reality.

The Legacy of the Unmade

Hollywood may call them failures. Fans call them dreams. Somewhere in between lies the truth. Unmade science fiction films are not dead, they're dormant. They exist in sketches, in anecdotes, and in the quiet influence they leave behind. For every movie that was canceled, there's another that borrowed its bones and ran with them.

Jodorowsky's lost Dune shaped the visual DNA of Alien and Blade Runner. The collapse of Microsoft's Halo project birthed District 9. Disney's Calling All Robots whispered its ideas into Pacific Rim. Even Faulkner's forgotten satire and Harryhausen's unrealized monsters left their shadows on the art that followed.

In that sense, Hollywood's trash heap is also its seedbed — creativity does not vanish when the money runs out; it mutates, finds new hosts, and survives.

There's something almost comforting about that. These phantom films are pure imagination, untouched by bad edits, test screenings, or box office failure. They exist in perfect form, suspended between thought and action. And maybe that is where science fiction belongs — halfway between reality and the dream of what could be.

The unmade film, like a message from a future we never reached, reminds us that progress is not linear. It's messy, full of false starts and forgotten brilliance. But those ghosts still work for us. They challenge every new generation of creators to aim higher, think more creatively, and take more risks. After all, every world begins as an idea, and some ideas are too big to stay on the page.