The Fly 1986 The Fall of Reason

A scientist’s experiment turns to tragedy in David Cronenberg’s “The Fly” 1986. This review explores ambition, transformation, and the cost of progress when intellect outpaces morality.

Science fiction has always tested the reach of human curiosity. It weighs discovery against responsibility with a cool eye. The field is a ledger where imagination must balance with cost. Every new device promises liberation and whispers a warning.

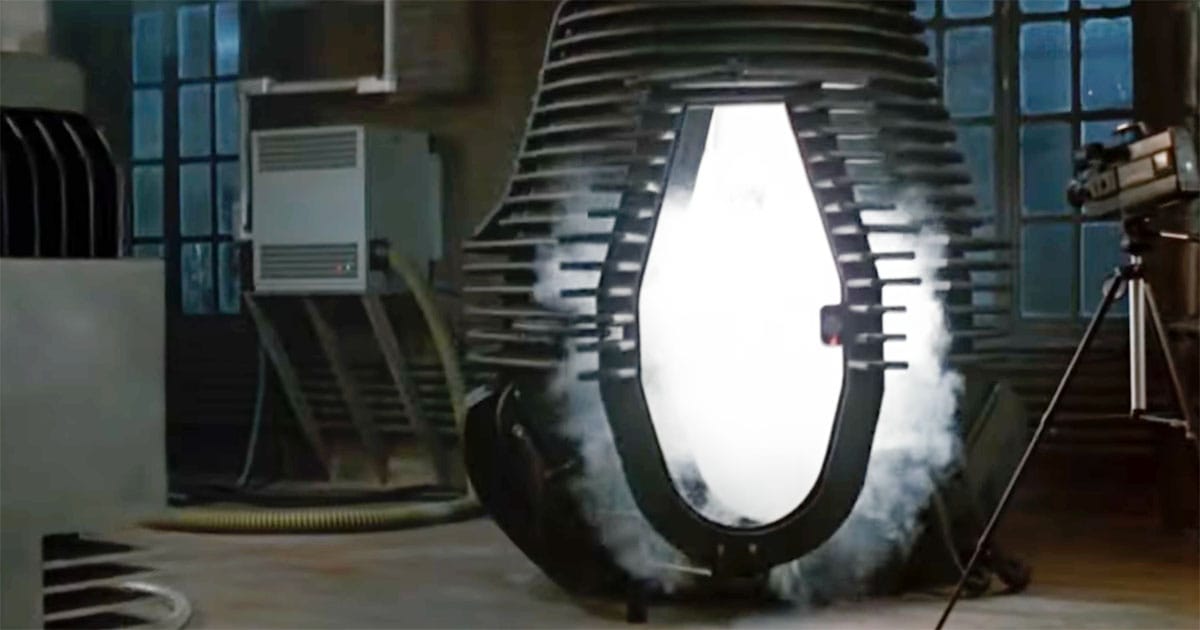

"The Fly" begins as a celebration of intellect and precision. A scientist refines teleportation and admires his own elegance. The machine shines and the equations sing. The result is not transcendence but contamination.

David Cronenberg treats the premise with clinical patience. He observes procedure and aftermath with equal care. His camera favors process over spectacle. The laboratory feels ordinary until it records the most extraordinary failure a mind can engineer.

This story is not about monsters from elsewhere. It is about a man whose talent outruns his judgment. Transformation exposes the moral deficit that lies hidden within his confidence. The body becomes the evidence, and the mind becomes the witness.

"The Fly" endures because it speaks calmly about ruin. It shows how progress without humility turns inward and consumes its maker. The film asks what remains of identity when method replaces wisdom — the answer is measured in loss rather than glory. Its caution feels earned, precise, and painfully hard to ignore today.

| Attribute | Value |

|---|---|

| Title | The Fly |

| Director | David Cronenberg |

| Writer | David Cronenberg, Charles Edward Pogue |

| Actors or actresses | Jeff Goldblum, Geena Davis, John Getz |

| Rated | R |

| Runtime | 1 h 36 min |

| Box Office | ~$60 million worldwide |

| U.S. Release Date | August 15, 1986 |

| Quality Score | 8.0 / 10 |

Synopsis

Seth Brundle is a young scientist whose brilliance hides behind an awkward manner. He believes he has solved one of the great challenges of modern physics.

His invention — a pair of teleportation pods — promises to move matter instantly from one point to another. The concept feels pure and elegant, a simple extension of logic into reality.

Brundle meets Veronica Quaife, a journalist who recognizes the scale of his achievement. She begins to record his progress, first as a scientific study and later as a personal connection. Together, they witness the first successful transfer of a living creature, a small victory that seems to confirm genius. In this moment of pride, Brundle decides to make himself the final test.

He enters the machine unaware that a single fly has joined him. The device performs perfectly. The error is invisible until it begins to rewrite his body. At first, he feels stronger and sharper, as though evolution has rewarded him for daring.

The change soon reveals its cruelty. His strength becomes frenzy, his intellect turns erratic, and his flesh begins to fail. The scientist who wished to conquer distance finds himself trapped inside his own mutation. The experiment succeeds, and the man disappears.

Themes

The Ambition of Knowledge

Seth Brundle's story is a modern echo of the oldest warning in science fiction. Knowledge pursued without restraint becomes its own undoing. Brundle begins his work with the best of intentions.

He wishes to change the world, to make distance irrelevant and motion instantaneous. Yet his devotion to progress blinds him to danger. What should have been a measured investigation becomes an act of faith in himself. The teleporter, built to serve man, becomes the instrument of his downfall because he never asks if the goal should be reached at all.

This theme has shaped the genre from Frankenstein to 2001. Science fiction often reminds its audience that intellect without humility leads to isolation. Brundle's fate is not punishment from above but a consequence born of arrogance. His discovery works perfectly. It is the man who fails.

The Body and the Mind

Cronenberg's fascination with the body turns the film into a study of identity. Every stage of transformation feels like an argument between flesh and reason.

Brundle's mutation is not only a physical event but a psychological one. The more his body changes, the less his intellect governs it. The scientist who once measured atoms begins to speak of destiny. His new strength deceives him into believing he has evolved beyond ordinary men when, in truth, he has reduced himself to instinct.

This conflict between the rational and the animal defines the movie's horror. It is not death that frightens but disintegration, the slow erasure of the self by the forces it once commanded.

Love as the Measure of Humanity

Veronica Quaife remains the emotional center of the story. Her role is neither savior nor victim but the conscience of the narrative. Through her eyes, the viewer measures what Brundle loses as his experiment advances.

Her compassion is patient and grounded, the last remnant of human warmth in a world of cold machinery. When she faces the final version of Brundle, the audience feels the collapse of intellect through her sorrow. The machine has perfected transport but destroyed connection.

Technology and the Illusion of Progress

The teleporter stands as a symbol of modern belief in technology's purity. It performs exactly as designed and exposes the flaw that design cannot predict, the human being who misuses it.

Cronenberg shows that machines are not moral or immoral. They are extensions of intention. In Brundle's hands, invention becomes confession. The device reveals more about its maker than about physics. Progress succeeds, and man fails.

Who Will Watch

"The Fly" speaks to viewers who value science fiction as inquiry rather than escape. It appeals to those who find fascination not in explosions but in consequences.

The film invites a thoughtful audience, one that prefers questions over reassurance. It does not flatter the viewer with easy morality or spectacle. Instead, it presents a world where ideas have weight and every discovery carries a moral price.Those who admire the intellectual lineage of writers like Arthur C. Clarke and Isaac Asimov will recognize the structure of thought beneath the horror.

Cronenberg's film is driven by hypothesis and result, by method turned against its maker. It is an experiment that plays out before the eyes of the audience, one that confirms the human tendency to reach too far. The terror is not supernatural. It is rational, predictable, and therefore believable.

The movie rewards patience and attention. Its pacing is deliberate and its imagery uncomfortable, yet every scene advances the argument that progress without humility becomes corruption. The viewer who seeks that balance between reason and fear will find the film both compelling and sobering. It is not for those who crave simple resolution. It is for those who wish to understand why tragedy so often follows invention.

The film also endures for its honesty about the human condition. It does not condemn science but asks for conscience to accompany it. In that way, it feels less like a warning from the past and more like a forecast that keeps coming true. Viewers who value thoughtful craftsmanship will appreciate its discipline, its restraint, and its refusal to sensationalize.

"The Fly" will attract men and women who grew up wondering what lies beyond the laboratory door. It belongs to the audience that respects science as a force that can illuminate or destroy, depending on the mind that guides it. The film's legacy is not built on fear alone but on reflection. It reminds its audience that understanding nature is only half the task. The greater challenge is to understand ourselves before the experiment begins.