"The Last Starfighter" and Early CGI

How "The Last Starfighter" used early CGI and a Cray X-MP supercomputer to pioneer digital visual effects, marking a turning point in how science fiction films created space battles.

Before the Pixels Took Over

In 1984, movie audiences encountered a science fiction film that looked familiar yet behaved differently. "The Last Starfighter" arrived during a period when space adventures followed well-established visual rules. Starships were photographed miniatures, explosions were optical tricks, and realism came from craftsmanship rather than computation. This film quietly challenged that assumption.

The story itself felt comfortably traditional. A young man proves himself worthy through skill, discipline, and courage, then answers a call beyond his ordinary life. What made the movie unusual was not its plot, but how it chose to visualize heroism. Instead of physical models, it relied on mathematics.

A Supercomputer Enters the Movies

The filmmakers made a decision that bordered on reckless for the time. Roughly 27 minutes of the film's space combat would be created with computer-generated imagery. This work was produced on a Cray X-MP supercomputer, a machine designed for advanced scientific research. Hollywood had rarely touched such technology.

The Cray X-MP filled an entire room and demanded extraordinary resources. Each frame required hours of processing, sometimes longer. Artists often arrived in the morning to discover whether their work had succeeded or failed overnight. The workflow rewarded patience, discipline, and careful planning.

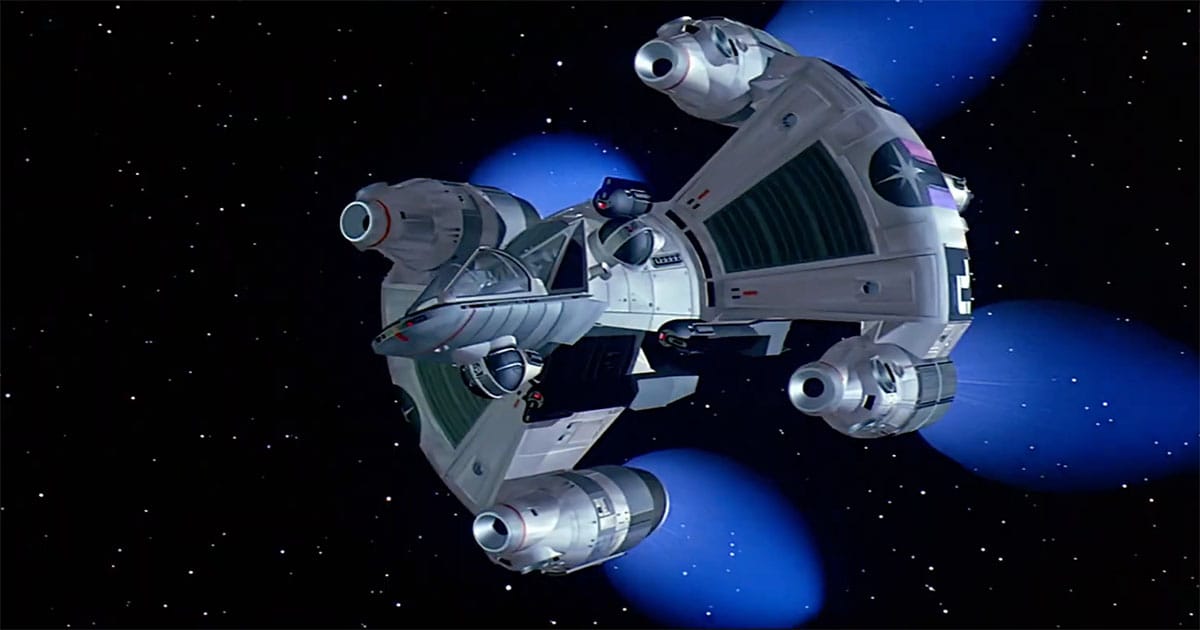

This approach eliminated many familiar tools. There were no physical models to light, no miniature cameras to reposition. Every ship, explosion, and maneuver existed only as data. The film became one of the earliest mainstream productions to trust computers with extended action.

The Look of a New Kind of Space

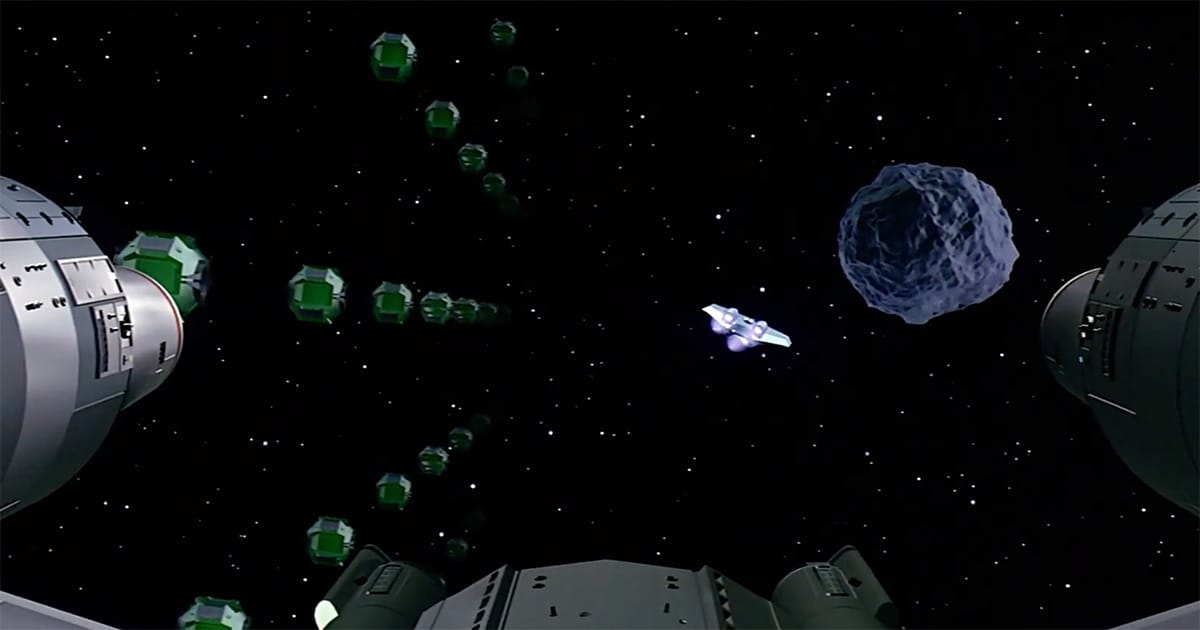

The resulting imagery stood apart from anything audiences had seen. Starfighters moved with smooth precision, their surfaces clean and sharply defined. Explosions expanded in perfect symmetry, free of drifting smoke or debris. Space felt ordered rather than chaotic.

At the time, some viewers sensed something artificial about the images. Yet the style aligned neatly with the film's themes. The hero's journey begins in an arcade, mastering a game of patterns and timing. The digital battles looked like the logical extension of that world.

Rather than undermine the story, the visuals reinforced it. Skill learned in abstraction became competence in reality. Discipline translated into responsibility. The film suggested that technology, when mastered, could serve higher purposes rather than replace human judgment.

A Risk That Changed Expectations

Hollywood reacted cautiously in spite of the experiment's success. The technology remained expensive, slow, and inflexible. Most studios returned to miniatures for the remainder of the 1980s, refining practical effects to remarkable levels. The industry was not ready to follow immediately.

Still, the lesson lingered. The film demonstrated that computer imagery could carry emotional and narrative weight. CGI no longer belonged only to charts, schematics, or brief demonstrations. It could depict danger, sacrifice, and victory.

When digital effects surged in the early 1990s, the groundwork had already been laid. Advances in processing power made computers faster and more practical. Filmmakers remembered that an earlier generation had already taken the risk. Confidence replaced hesitation.

Today, the film occupies a transitional place in science fiction history. Its visuals show their age, yet its ambition remains striking. It bridges handcrafted spectacle and digital imagination. "The Last Starfighter" helped move science fiction cinema from models on strings to worlds built from numbers, and the genre never truly turned back.