Why "Fahrenheit 451" Still Matters in the Age of Noise

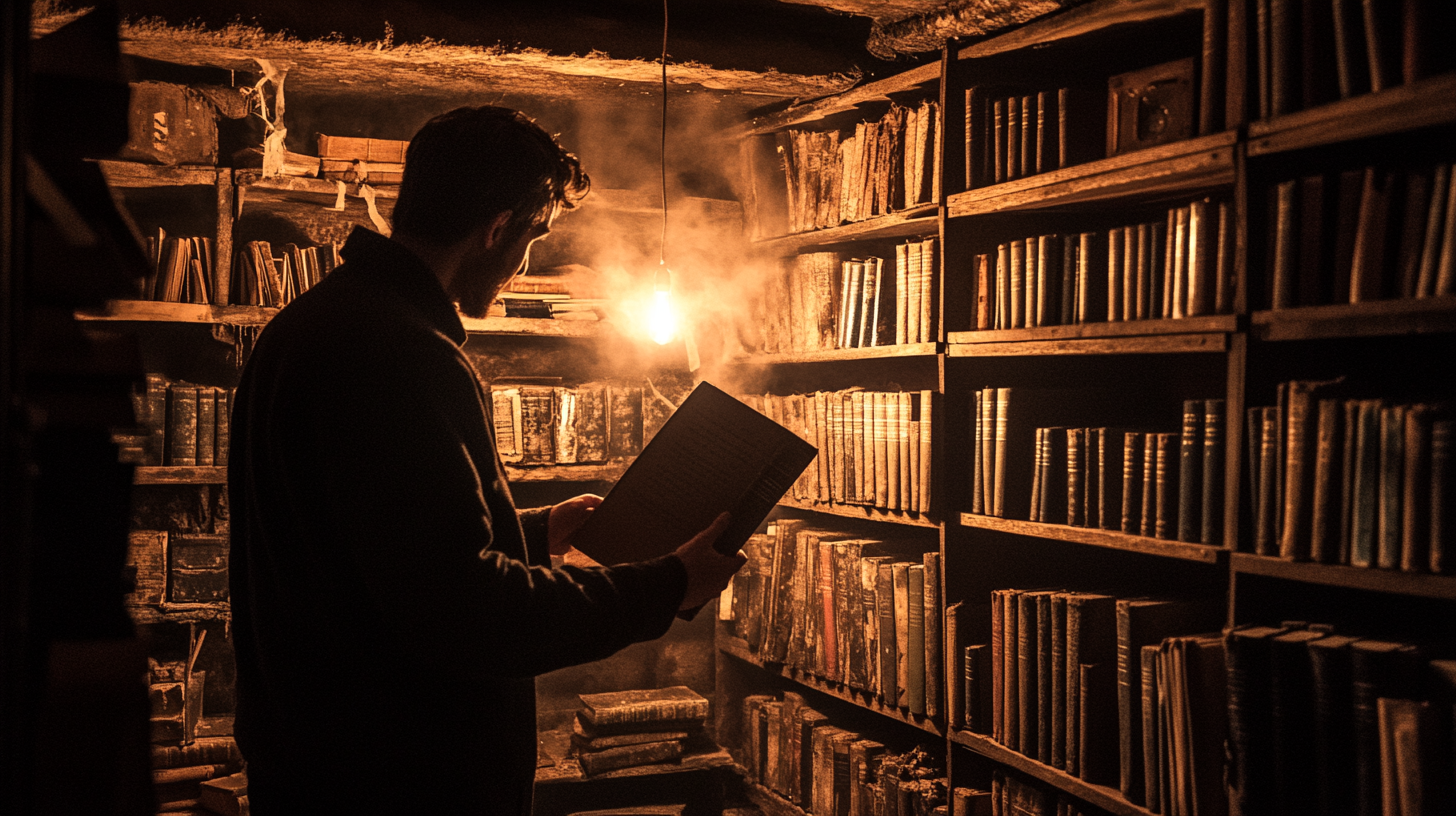

Bradbury’s "Fahrenheit 451" remains a chilling reflection on censorship, mass distraction, and moral decline in a world that trades truth and memory for comfort and silence.

In 1953, when "Fahrenheit 451" first reached bookshelves, America stood at a cultural crossroads. The Cold War cast a long shadow across the country, and the fear of subversion was not limited to enemy agents or atomic weapons. Suspicion had reached into libraries, lecture halls, and living rooms. Against this backdrop, Ray Bradbury offered a sobering vision of a future where the written word was not only unwanted but actively extinguished.

Bradbury, already known for "The Martian Chronicles," approached science fiction less as a laboratory of tomorrow and more as a moral barometer for today. His interest was never in predicting gadgets but in warning against spiritual and intellectual collapse. "Fahrenheit 451" pushed these concerns to their most extreme conclusion, sketching a society that traded contemplation for comfort and memory for spectacle.

This review examines "Fahrenheit 451" through the lens of its themes, structure, and imaginative elements. Though the novel has been discussed in classrooms and op-eds for decades, it remains a uniquely haunting story with a clear message. Its relevance has outlasted its predictions. We aim to consider not only why this book mattered in 1953, but why it still compels readers to think more carefully about what they read, and what they forget.

Thematic Foundations

"Fahrenheit 451" is not a story about firemen or even books, in the literal sense. It is a story about forgetting—about what happens to a culture that chooses comfort over complexity. At its heart lies a study in willful ignorance. Bradbury builds a world where censorship is not imposed from above by a tyrannical state, but embraced from below by a public that has grown tired of thinking.

Censorship, in this case, is not just about burning pages. It is about burning time, burning silence, burning the slow work of contemplation. Bradbury never portrays books as magical objects. Rather, they are vessels of memory, challenge, and meaning. When a society discards them, it loses more than knowledge. It loses its ability to ask why.

One of the novel's most enduring themes is conformity. In Bradbury's imagined future, dissent is not crushed violently—it is laughed off, ignored, and erased. Individual thought becomes suspect not through surveillance, but through social pressure. The worst crime is not rebellion. It is curiosity.

Bradbury's use of fire as a symbol gives the book its philosophical spine. Fire is presented first as destruction. It is swift, clean, and final. But Bradbury does not stop there. As the story progresses, fire also becomes a symbol of purification, warmth, and eventual renewal. The same force that erases can also illuminate, depending on the hand that holds it.

The critique of mass media is no less central. Walls of television chatter and seashell earpieces fill every moment with noise. In this world, distraction replaces reflection. Bradbury saw the danger not in technology itself, but in its misuse—the way it can replace real conversation with shallow spectacle. What he feared was not an authoritarian clampdown, but a population that forgets how to think and no longer cares to remember.

These themes did not arise in a vacuum. Bradbury was writing at a time when postwar optimism masked deep anxieties. The rise of television, the Red Scare, and the push for suburban uniformity were shaping a society eager to avoid discomfort. "Fahrenheit 451" captured that tension in fiction, offering a warning that remains sharp even today. It reminds us that forgetting can be a choice—and a dangerous one at that.

Building and Imaginative Mechanics

Bradbury's vision of the future in "Fahrenheit 451" is crafted not with elaborate blueprints, but with focused, evocative design. The world he presents is compressed into clean pavements, odorless incinerators, and homes sealed against conversation. There is no clutter in this future, and that sparseness is intentional. Everything unnecessary—especially thought—has been cleared away.

The firehouse, for example, is not just a workplace. It is a ritual chamber for erasing the past. Its technology, including the infamous mechanical hound, reflects a cold precision that mirrors the emotional detachment of its users. These machines are not awe-inspiring. They are clinical. They do not expand the imagination. They contain it.

Bradbury's most effective speculative touch may be the parlors filled with wall-to-wall screens. These are not advanced because of what they show, but because of what they replace. They turn the living room into a space where reality is drowned out by manufactured presence. These devices are not malevolent. They are mundane. That is what makes them dangerous.

The world Bradbury builds is small, deliberate, and symbolic. He leaves out grand technologies of war or space exploration, choosing instead to focus on domestic tools that reshape daily life. In doing so, he shows how the future can be emptied out not by conquest, but by design.

Style Language and Literary Technique

Ray Bradbury wrote with a pen dipped in flame. His prose in "Fahrenheit 451" is urgent, compact, and often lyrical. Unlike his contemporaries, who favored restrained exposition or scientific rigor, Bradbury embraced metaphor and rhythm. His sentences do not march—they leap, often unexpectedly, from image to image, carrying the reader on a wave of unease and wonder.

This stylistic boldness drew mixed reactions upon publication. Some early critics praised what they called "verbal fireworks," while others found the language overwrought. Still, Bradbury's voice arrests the reader. His syntax is not always conventional, but it never feels accidental. He uses language not just to describe, but to unsettle.

The novel's structure is lean, divided with precision, and paced like a tightening coil. There are no diversions, no subplots to soften the blow. Every scene serves a thematic or emotional purpose. Dialogue often feels abstracted, like pieces of a riddle, which deepens the dreamlike tension of the world. Bradbury's characters speak in clipped tones, as if words themselves are growing scarce.

Symbolism plays a large role in the novel's impact. Fire, paper, and mirrors recur throughout, building a network of meaning without extended commentary. Bradbury trusts the reader to recognize pattern and significance, even as the world within the novel loses its grip on both.

While some readers may find the language heavy-handed, that intensity suits the material. "Fahrenheit 451" is not a quiet book. It is an alarm bell, and Bradbury writes with the volume turned high. His style demands attention and rewards it with images that linger long after the story ends.

The Fire Still Burns – Legacy and Critical Appraisal

When "Fahrenheit 451" first appeared, it was met with a mixture of admiration and unease. Readers and critics alike recognized its imaginative power. Many hailed its warning against censorship as not just timely but necessary. Reviews in science fiction magazines praised Bradbury's vision, while more traditional outlets raised concerns about its tone. Some found the book heavy-handed or overwrought. Others dismissed its style as melodramatic. Yet even these critics could not ignore its impact.

As decades passed, the novel took on a second life in schools and universities. It became one of the few science fiction works routinely taught alongside literary classics. Educators embraced it not just for its warnings, but for the way it provoked questions about freedom, responsibility, and the role of media in daily life. Students found in it a story that did not feel like homework. It read more like a signal flare.

In an age of scrolling headlines, algorithmic feeds, and digital fatigue, the story of a world without books seems less like fiction and more like foresight. Though some of Bradbury's inventions may feel quaint today, his larger message has only grown louder. He did not need computers or satellites to tell us what to fear. He needed only to show what happens when we stop thinking for ourselves.

"Fahrenheit 451" remains essential not because of its gadgets or guesses about the future, but because of its moral urgency. Bradbury did not write to predict. He wrote to warn. And his warning has lost none of its power. This is a novel that still asks the right questions. It still challenges the reader to turn down the noise, to open a book, and to remember what it means to care whether something is true.